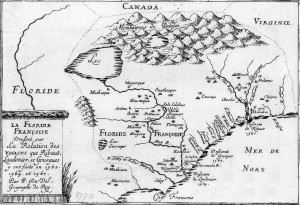

We were pleased to hear this week of the release of a trailer from Aperio Productions for their new film, The Massacre at Matanzas, a documentary about the 1565 massacre of the French Huguenots at Ft. Caroline (modern day Jacksonville, Florida). The film recounts the history of Captain Jean Ribault‘s voyage to the New World in 1562, the establishment of a colony by French Huguenots in 1564, and the massacre of the settlers at the hands of the Admiral Pedro Menéndez in 1565.

Ribault had been commissioned by Charles IX, King of France, “to discover and vieu a certen long coste of … the land called la Florida.” A French presence in the New World did not sit well in Spain, so Menéndez was commissioned by Phillip II, King of Spain, to sail to Florida and “to hang and slaughter” any Huguenots he found there . When Menéndez found the Huguenots, he offered them a choice—convert to Roman Catholicism, or die. When they refused, Menéndez carried out his mission with a barbaric zeal that still makes us wince even four centuries later.

Because the period of French Colonial Florida was so brief, it is largely overlooked in our history books, and the focus shifts instead to Jamestown, Virginia, which was founded a full 45 years after Ft. Caroline. We are pleased that Aperio has revisited this formative period in American history to honor the memories of the Huguenots who “loved not their lives unto the death” (Revelation12:11). We invite our readers to discover more about this period either by following the release of the Aperio production (in which we participated), or by reading Jean Ribault’s account in the English translation of his book, The Whole & True Discouerye of Terra Florida, available at the University of Florida Digital Collections by clicking on the link.

The period is filled with remarkable ironies, not the least of which is the subsequent voyage of Dominique de Gourgue in 1567 to avenge the deaths of his fellow countrymen after news of the massacre reached France. It was one thing for the French to kill their own Huguenots at home (see the Massacre of Vassy that occurred in 1562 while Ribault was still en route to Florida), but quite another for Spaniards to kill French Huguenots abroad. De Gourgue, himself a French Roman Catholic who had opposed the Huguenots in France, sailed on a military expedition to Florida to avenge the murders of the Huguenots—not because he shared their religion, but because he shared their homeland. The Spanish massacre was not only a crime against humanity, but was also an offense against the French Crown. Charles IX had not mustered the courage to defend his crown rights in New France, so de Gourgue took it upon himself to defend the honor of France by finding and punishing the perpetrators of the horrific massacre of the Huguenots.

Equally ironic was the practice of the Florida natives, who—after experiencing both French Protestant and Spanish Roman Catholic explorers—came to prefer the French to the Spanish, and required crews of arriving ships to sing Huguenot hymns as a condition of debarkation, to prove that they were French. Thus did de Gourgue and his Roman Catholic crew find themselves singing Protestant Hymns for the Native Americans in order to prove that they were French, so that they could get on with the business of killing Spanish Roman Catholics to avenge the murder of French Protestants (The Whole & True Discouerye, Introduction, p. xlv).

What we will examine today is the influence of the preceding centuries on both French and Spanish culture, which influence could lead Roman Catholic de Gourgue to exhaust his personal wealth for the sake of French Huguenots, and lead Menéndez to think that “evangelization” of the New World must take place by the business end of a bloody Spanish sword rather than by the Sword of the Spirit, the Word of God (Ephesians 6:17).

The Background

Sixteenth century Europe, reeling from the birth pangs of the Protestant Reformation and Roman Catholicism’s answer to it in the Counterreformation, was a cauldron of political, social and religious upheaval. Relations between nations were subject to the religious inclinations of their respective monarchs, and relations between monarchs and their people were driven in part by the degree to which the populace found the monarchy sympathetic to their religious convictions. This state of affairs also affected relations between citizens—in the Old World and the New. Depending on circumstances, national interests might trump religious as easily as religious interest might trump national. Additionally, the culture and identity of each nation had been forged in the crucible of the uniquely formative events of the preceding centuries. It is important to understand those formative events as prologue both to the 1565 massacre and to de Gourgue’s mission in 1567 to avenge it.

France had only in 1453 emerged from 100 Years War with England, and Spain had only in 1492 emerged from the Spanish Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula, a conflict with the Moors that had lasted almost 800 years. The national identity of each country was forged during these conflicts. The 100 Years War began as a territorial dispute, and produced Joan of Arc as a national heroine and Roman Catholic martyr. The Reconquista was both a religious and a territorial war and gave rise to El Cid as a national hero. It was also during the Reconquista that St. James began to be heralded as “the Moorslayer,” the patron saint of Spain. When Spain had been finally liberated by “the bloody sword” of Reconquista, instead of finding its sheath, the sword simply went looking for another target for its “evangelism.” It did not take long to find one.

With the rise of Protestantism as a social, religious and political force at the dawn of the 16th century, the stage was set for a religious conflict that would test the ties between nations and within them. Relations between compatriots of different religions, or between coreligionists of different nationalities, could alternate between lethal hostility and prodigious self-sacrifice, depending on the lens through which those relations were defined, and the culture that had formed the lens itself. Exploring this dynamic, and the unique culture and sociology behind it, will help the reader understand the prologue to the Ft. Caroline Massacre in Florida and its aftermath.

The Massacre

In 1562, the young King Charles IX appointed Captain Jean Ribault, on behalf of the French people,

“to discover and vieu a certen long coste of the West Indea, from the hed of the land called la Florida … to the honnour and praise of theire Kinges and prynces, and also to thincrease of great proffite and use of their comon wealthes, counteris and domynions.”[1]

Captain Ribault and his crew, comprised largely of French Huguenots, landed in Florida† on May Day, 1562, claiming this “goodly newe France”[2] for the King, and erecting stone columns commemorating the landing.[3] This news was not received well in Spain; when King Philip II heard of this, he commissioned Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to put an end to the French presence in Florida and reclaim the territory for Spain. On his authority, Menéndez was to come “to this land to hang and slaughter all Lutherans* who were found in it.”[4] In October of 1565, after the Spaniards had taken Ft. Caroline (modern day Jacksonville), where Jean Ribault and the Huguenots were encamped, Ribault sued for peace, correctly arguing that the kings of France and Spain were not at war, but were “Hermanos.”

Menéndez responded, agreeing with Ribault—that the two countries were not at war, and therefore Catholics of both nations were friends—

“…but because you are of the New Sect, we take you for enemies, and we have only war, blood, and fire, between us, which we will prosecute with all cruelty whether at sea or on land.”[5]

Having so responded, Menéndez completed his mission. Ribault’s “splendid beard was cut off and part of it sent to Philip. His head was quartered and his body burned with those of his slain companions.”[6] Only 16 people were spared: women, infants, and children under fifteen years of age, as well as anyone who would acknowledge that he was Catholic.[7] Menéndez is alleged to have hung this epithet at the scene of the murders: “Not as Frenchmen, but as Lutherans.”[8] As his own words indicate, Menéndez’ motives were more religious than nationalist in nature.

The French, of course, were aghast when the news of the massacre reached European shores. Dominique de Gourgue (himself a French nobleman, soldier and a Roman Catholic), set sail in August 1567 from France to Florida to punish the Spaniards for the crime. So daring and honorable was his mission, that even the Spanish chronicler had to pay it homage: “enflamed by the zeal of the honor of his homeland, he determined to exhaust the wealth of his household in that enterprise, expecting nothing more than to avenge” the honor of France.[9] That de Gourgue’s motivation was patriotic rather than religious is well attested. His family insisted that that de Gourgue’s “expedition to Florida was a patriotic deed in which religious zeal had no part,”[10] as does the historical record of de Gourgue’s own words to his crew under sail:

“I thought you sufficiently jealous of the glory of your Fatherland, to sacrifice even your own life on an occasion of this importance!” [11]

In April 1568, De Gourgue completed his mission and executed the Spaniards at the fort renamed San Mateo, which had been built on the site of Ft. Caroline, hanging them from the same trees from which the Huguenots had been hung three years earlier.[12] De Gourgue posted an epithet of his own, in answer to Ménendez’ atrocity: “Not as Spaniards, but as Traitors, and Murderers.”[13] Clearly de Gourgue’s motives were not of a religious nature, and one historical record suggests that he may have gone out of his way to eliminate religious zeal as a possible motive by writing, “Not as Spaniards, nor as Marannes,” a disparaging term for Jewish or Moorish converts to Roman Catholicism.[14] To rectify the offense against the crown was the sole mission of his patriotic zeal.

We highlight this contrast between the motives of Menéndez and de Gourgue to emphasize the conflicted nature of relationships between citizens of Europe at the time: political and religious affections on the continent were so unpredictable that relations between compatriots of different religions could swell to the noble heights of de Gourgue’s zeal on behalf of Ribault and the settlers. Yet relations between coreligionists of different nations could plumb the depths of de Gourgue’s bloody vengeance executed against the fellow Roman Catholics of Menendez’ garrison at Ft. San Mateo. On the other hand, congeniality between Roman Catholics of different nationalities was sufficiently warm that Menéndez could pardon any French Roman Catholic encroaching on Spanish territory in Florida. Yet the enmity borne toward those of “the New Sect,” was of such a barbaric nature that, as one eyewitness recounts, Menéndez and his men could hack the Hueguenots to pieces and hurl their body parts toward those not yet captured, as a means of eliciting despair.[15]

The Ft. Caroline Massacre was not an isolated incident, and as brutal as it was, it was not inexplicable (though no less inexcusable) in its context or in its era, and did not take place in a vacuum. Cultural developments—both political and religious—in medieval Spain bore heavily on the barbaric brutality of Menéndez’s response to French encroachment in “New Spain,” and similar development in medieval France would have factored significantly into de Gourgue’s response to Spanish encroachment in “New France.”

French Cultural Developments during the Hundred Year War as a Prologue to Captain de Gourgue’s Voyage

In the century preceding the Ft. Caroline Massacre, France had emerged victorious from the devastation of the Hundred Years War with England, with Joan of Arc as a new heroine and martyr of the French people. But France had emerged not solely as a victorious culture or kingdom, but as a victorious nation-state. In early 15th century France, the midpoint of the war, writes Deborah Fraioli, “Few historians would admit that nationalism as yet existed,” but the war had,

“perhaps from the sheer duration of the struggle, been altered, for some, into an essentially nationalistic war. French patriotism had certainly been aroused, although a name for the sentiment would lack for a name in French until the end of the century.”[16]

It is notable that the foundations of French nationalism and patriotism were laid during the victories, trial and execution of Joan of Arc. “It has been said with some justice,” Faioli continues, “that Joan of Arc both created nationalism and arose because of it.”[17]

So desirous were the French of any ray of hope in the seemingly endless war, that Joan of Arc became the subject of soaring poetic adulation even before her trial and execution. In her 1429 poem, The Song of Joan of Arc, French writer Christine de Pizan expressed high admiration for Joan, and even higher ambitions. “Greater than all the knights” is she (Stanza 44). De Pizan not only lauded Joan’s military victories (Stanzas 33 & 36), but that she had restored the King to his rightful throne (Stanzas 6 & 48, 49), would expel the English invader (Stanzas 39, 40, 41 & 45), would liberate Paris (Stanzas 53 & 54), would restore the Church and bring peace to Christendom (Stanza 42), and conquer the Holy Land (Stanza 43). To resist Joan was to resist the will of God—an exercise in futility, de Pizan warned (Stanzas 47 & 51). These were the first rays of the dawn of French patriotism and nationalism, and Joan of Arc was at their center. As inspired as the French people were at the rise of Joan, her heresy trial and execution would even more firmly seal her fate as an enduring symbol of the nation. Joan was tried and executed in a venue that was later determined to be wholly unjust.[18] Thus was Joan of Arc, the symbol of French nationalism and pride, tried at the hands of foreigners and executed.

In light of the recent origins of French nationalism and the demise of its progenitress, the indignation of the French people collectively, and of de Gourgue in particular, to the execution of French Huguenots in Florida—and that, solely on account of their faith—is better understood. The death of their own compatriots, engaged in a lawful expedition on the authority of King Charles IX himself and with no trial, followed by an execution of such grotesque excess of brutality at the hands of the Spaniards, would surely inflame the passions of patriots on the continent, in whose collective memory the martyrdom of Joan of Arc was so fresh.

But de Gourgue would have even greater reason for his consuming zeal. Not only had he been captured and ill-treated by the Spanish during the Italian Wars, but he was also of Gascony, a region in southwest France that had suffered most under the occupation of the English in the 100 Years War. Just as his blood ran hot against England, “[h]is Gascon blood ran hot against the name of Spain”[19], too. Gascony had suffered greatly”, during the war, and had contributed significantly to France’s final victory. It was, after all, the party of Gascon noble, Bernard of Armagnac, the chief province of Gascony during the Hundred Years War, that aided Joan of Arc against the Burgundians and marched on Paris with King Charles at the head.[20] Joan of Arc was so identified with de Gourgue’s home that the English derisively called her “the Harlot of Armagnac.”[21]

With this backdrop, de Gourgue’s zeal is entirely understandable, and in this context, it is more clearly understood why de Gourgue would implore his crew en route to Florida, “I thought you sufficiently jealous of the glory of your Fatherland, to sacrifice even your own life on an occasion of this importance!” This zealous patriotism and jealous nationalism had been in the making for centuries, and the affection Joan of Arc had for Gascony would have been played no small part in it.

Spanish Cultural Developments during the Reconquista as a Prologue to Admiral Menéndez’ Voyage

For the eight centuries leading up to Menéndez’ voyage to Florida to eliminate the French colony, Spain had been struggling under the weight of Moorish hostilities. The Muslims had invaded the Iberian Peninsula, and gradually encroached upon all of Spain from Gibraltar to the Pyrenees. The first formal resistance to the Moorish advance was organized by Pelayo, the first king of Asturias,[22] a region situated on the northern coast of Spain. Pelayo defeated the Muslim invaders early in the eighth century, at the pivotal Battle of Covadonga.[23] Thus began the Reconquista, a struggle for ideological supremacy that would last nearly a millennium—the Muslims were not completely expelled from Iberia until 1492 at the Battle of Granada by the united armies of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile,[24] also known as Ferdinand the Catholic, and Isabella the Catholic,[25] the Catholic Monarchs. Notable is the fact that the final battle for supremacy on the peninsula was not waged by a Spanish nation, per se, but jointly by the Aragonese and Castillian crowns. At the Fall of Granada, the concept of Spain as Spain or as España, was still nearly 400 years yet in the future. Even in the 1812 Spanish Constitution, when the idea of an hispanic nation was codified (i.e., “Nacion española”), Fernando VII was identified as “the King of the Spains,”[26] a plurality of territories that encompassed not only the greater part of the Iberian Peninsula, but also a vast overseas empire.[27]

In contrast to the emergent nationalism of 15th century France after the Hundred Years War, the Reconquista had forged in Spain a religious zeal for the survival of Roman Catholicism on the peninsula. At the turn of the First Millennium, only two centuries into the Reconquista, people of Spain were coming to the inevitable conclusion that “relations between Christians and Muslims were necessarily and justly hostile, that Christian warfare against Islam bestowed positive spiritual merit on the participant, and that Muslims should be driven out of Spain.”[28] In the midst of this lengthy religious conflict emerged the heroic figure of El Cid, and the cultural devotion to Santiago (St. James), the patron saint of Spain. It was here that the concept of violent and bloody conquest as a form of evangelism took shape. Santiago was surnamed Matamoros, the Moor-slayer,[29] and in the Poem of El Cid, Christians are said to call on the name of Santiago, and the Muslims on the name of Mohamad.[30] The poet instructs the Spanish people that “This is God’s will, and of that of His saints: See the bloody sword, see the sweaty horse, this is how you defeated the Moors in the field.”[31]

Santiago’s bones were alleged to have been found at Compostela,[32] and the Order of the Knights of Santiago was formed under the banner of Santiago of Compostela with the motto, Rubet ensis sanguine Arabum, “The sword is red with the blood of Arabs,”[33] and with a symbol that is little more than a bloody, cross-shaped dagger (pictured below).

Santiago himself was alleged to have miraculously appeared at the legendary battle of Clavijo to rally the King of Asturias and his troops, and the list of Santiago’s “military achievements soon grew longer and longer, and by the end of the 16th century he had surpassed the performance of every other heavenly warrior.”[34]

Thus, at the tip of the blood-red dagger of St. James was formed in the Spanish psyche the concept and necessity of bloody, ruthless conquest as the means of defending the Catholic religion and spreading it to the world. It took centuries to form the concept, and the fact that it first originated in the region of Asturias at the Battle of Covadonga is not insignificant: Admiral Menéndez was born in Asturias,[35] the birthplace of the Reconquista. The flagship of his Florida conquest was the San Pelayo, named after the first King of Asturias, the hero of the Battle of Covadonga.

“The conquest of Florida was a family affair and a regional enterprise. More exactly, it was a family affair of some nine major Asturian families, intricately interrelated by blood and marriage. The whole of the northern Spanish coast … took part in the preparation of the … Menéndez expedition. Most of the chief civil and military subordinates of Pedro Menéndez were Asturian…”[36]

To Menéndez, the conquest of Florida was a projection of the Reconquista onto the territories of the New World. It is not without reason that historian John Fiske called him “the last of the crusaders.”[37]

Although the Reconquista certainly originated in the Kingdom of Asturias, it imbued all of Spain with the same mentality. It is no surprise then, that in the waning years of the Reconquista, The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, or as it is commonly known, the Spanish Inquisition, complete with all the bloody zeal that the national cult of Santiago could inspire, was established by papal decree in 1478.[38] The Spanish Counterreformation would be born in Spain, as well, under the leadership Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, the Society of Jesus. He, too, was a product of the Reconquista, born just one year before the Fall of Granada. As with Menéndez, it can also be said of him,

“the single most important background influence on Loyola’s early development was the centuries-long Spanish military struggle against the Moors, known as the Reconquista, the war of reconquest. The pressures of that protracted struggle shaped Loyola and the caste he was born into, instilling into them the ancestral attitudes and values of … endurance, a rigid, intolerant, militant Catholicism, self-sacrifice, loyalty and dour hardihood.”[39]

It is notable that although King Philip II was a patron of the Jesuits, he was not originally eager to send them to the New World for fear of imposing on the Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians already present in Mexico and the southern continent.* Menéndez, after removing the Huguenot threat, appealed emphatically to the King to send Jesuits to convert the Indians, complaining that so much could be accomplished if the Jesuits would only come.[40] When the Jesuits finally came and encountered violent resistance to their overtures, Menéndez planned and executed a mission of reprisal to punish the Indians for what they had done to the Jesuits.[41] Thus did the Reconquista come to the New World—on the ships of Menéndez, the man of Asturias, “the last of the crusaders.”

The Vassy, Ft. Caroline and Paris Massacres in the Context of French and Spanish Roman Catholicism

It would be a mistake, of course, to think—on account of de Gourgue’s zeal—that French Roman Catholicism was of a softer form than the Roman religion of Spain, hardened as it was by the rigors of Reconquista. The false religion of Roman Catholicism that had dominated the Iberian Peninsula was fully present in France. Duke Henry of Guise—erstwhile employer of de Gourgue, and perpetrator of the Huguenot Massacre in Vassy while Ribault was en route to Florida—was head of The Catholic League (also known as The Holy League) which was formed for the eradication of Protestants from Catholic France during the Protestant Reformation. Pope Sixtus V, Philip II of Spain, and the Jesuits were all supporters of this Catholic party. The Catholic League’s cause was fueled by the doctrine Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salus (outside the Roman Catholic Church, there is no salvation), saw its fight against Huguenots as a Crusade against heresy.

We cannot fail to see the form of this same false religion in the aftermath of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1574:

“The severed head of Coligny was apparently dispatched to Pope Gregory XIII, … and Pope Gregory XIII sent the king a Golden Rose. The Pope ordered a Te Deum to be sung as a special thanksgiving (a practice continued for many years after) and had a medal struck with the motto Ugonottorum strages [Huguenot Slaughter] 1572 showing an angel bearing a cross and sword next to slaughtered Protestants.” (see image below).

That is the religion of the Spanish construct of Santiago, and of Joan of Arc, who inspired Pizan to write of her, “She will destroy the unbelievers … and the heretics with their vile ways, … she will have no pity” (Stanza 42). This was as firmly written into the French Roman Catholic psyche as was the bloody dagger of Santiago written into that of the Spanish Roman Catholic.

Conclusion

The intent of this post is to cast Pedro Menéndez’ voyage and massacre in the light of its natural religious context of 16th century Spain, and the culture that had developed there over the course of the previous eight centuries of Reconquista. The intent is also to put Dominique de Gourgue’s voyage to avenge the Huguenots in its natural patriotic context of 16th century France, and the culture that had developed there over the preceding centuries in the Hundred Years War. Neither voyage can be fully understood apart from these.

The irony of Roman Catholic de Gourgues sailing to Florida and singing Protestant hymns in order to kill Spanish Roman Catholics to avenge the murder of French Protestants abroad at a time when the French Roman Catholics were willing to murder French Huguenots at home (Vassy, 1562; Paris, 1574) is also explained. The execution of Joan of Arc on religious grounds by foreigners was sufficient to elicit patriotic sympathies toward Menéndez’ victims in “New France,” while the memory of Joan of Arc’s victories was sufficient to foment French Roman Catholic zeal against the “enemies of true religion” at home. The irony is rich, of course, but it is not paradoxical or unexplainable.

We hope our readers will join us in looking forward to the release of Aperio Productions’ new film, The Massacre at Matanzas, in which this brief period of French Colonial Florida will be more fully recognized, and the memory of the Huguenot martyrs more fully acknowledged.

Footnotes:

[1] Ribault, Jean, The Whole & True Discouerye of Terra Florida (London ©1563) reproduced by the Florida State Historical Society, 1927) 53-54

† “Florida” is a generic term for the eastern seaboard of North America, including modern day Florida, Georgia and South Carolina

[2] Ribault, 61

[3] Ternaux-Compans, H., Recueil De Piéces sur La Floride: Voyages, Relationes, et Mémoires Originaux Pour Servir A L’histoire De La Découverte De L’Amérique, “La Reprinse De La Floride Par Le Cappitaine Gourgue,” (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, Libraire-Éditeur, ©1841) 301

* “Lutherans” was a generic term for “Protestants”

[4] Andrés González de Barcia Carballido y Zuñiga, Ensayo chronologico, para la historia general de la Florida (Madrid, Span: En la Oficina Real, y á Cost de Nicolas Rodriguez Franco, ©1723) 75-76; in the original: “…que viene á esta Tierra á ahorcar, y degollar todos los Luteranos, que hallare en ella …”

[5] Barcia, 86

[6] Blackburn, William Maxwell, Admiral Coligny: and the rise of the Huguenots, Volume 2 (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, ©1869) 93

[7] Barcia, 81, 86

[8] Barcia, 136 (“No por Franceses, sino por Luteranos.”)

- Various claims are made of de Gourgue’s religious affiliation, but it appears that his family defended his Roman Catholic bona fides: “M. le Vicomte de Gourgues, the present representative of the family, desirous of vindicating the orthodoxy of his ancestors, and, in particular, of so illustrious a relative as Dominique de Gourgues, has given to the public incontrovertible proofs that the whole family was eminently Catholic, that Dominique lived and died in the faith…” (The Catholic World: A Monthly Magazine of General Literature and Science, Vol XXI, April – September 1875, (New York: The Catholic Publication House, ©1875), 704)

[9] Barcia, 134

[10] The Catholic World, 704

[11] de Charlevoix, Pierre-François-Xavier, Histoire de la Nouvelle France, vol. I, (Paris: Chez Rolin Fils, Libraire, Quai de Augustins, à S. Athanase, ©1744) 97; “J’ai compté sur vous, je vous ai cru assez jaloux de la gloire de votre Patrie, pour lui sacrifier jusqu’a votre vie en une occasion d cette importance…”

[12] Ternaux-Compans, 357

[13] Barcia, 136 (“No por Españoles, sino por Traidores, y Homicidas”)

[14] Reprinse has it as “Je ne faicts cecy comme à Espaignolz, n’y comme à Marannes; mais comme à traistres, volleurs et meurtriers,” “Not as Spaniards, nor as Marannes, but as traitors, robbers and murderers.” “Marannes” was a disparaging word of reproach used to describe Jewish or Moorish converts Catholicism. A similar sentiment might be conveyed in the US vernacular as “Not as Americans, not even as Protestants, but as, etc…”

[15] Gaffarel, Paul, Histoire De La Floride Française, “Histoire Mémorable Du Dernier Voyage En Floride par Le Challeux,” (Paris: Librairie De Firmin-Didot Et CIE, ©1875) 468. Challeux writes, “Lors ceste furieuse troupe reietta sa colere et sanglant despit sur les morts, et les exposerent en monstre aux François qui restoyent sur les eaux, et taschoyent à navrer le cœur de ceux desquels ils ne pouvoyent, comme ils eussent bien voulu, desmembrer les corps ; car, arrachant les yeux des morts, les fichoyent au bout des dagues, et puis avec cris, hurlemens et toute gaudisserie, les iettoyent contre nos François vers l’eau.”

[16] Fraioli, Deborah A, Joan Of Arc And The Hundred Years War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, ©2005) 55

[17] Fraioli, xxviii

[18] Murray, T. Douglas, Jeanne D’arc, Maid of Orleans Deliverer of France: Being the Story of Her Life, Her Achievements, and Her Death As Attested on Oath and Set Forth in the Original Documents, “Sentence of Rehabilitation” (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, ©2006) 303-307

[19] Blackburn, 94

[20] A History of France, (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, ©1853) 46

[21] Warner, Marina, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism, (University of California Press, ©1981) 96-116

[22] Fernández, Juan Gil; Moralejo, José Luís; de la Peña, Juan Ignacio Ruiz, Crónicas Asturianas: (Crónicade Alfonso III (Rotense y “A Sebastián”). Crónica Albeldense (y “Profética”), (Universidad de Oviedo, Jan 1, 1985) 247

[23] Fernández, et al, 34-35

[24] Ertl, Alan W., Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration, (Boca Raton, FL: Universal Publishers, ©2008), 286

[25] Charles George Herbermann, Edward Aloysius Pace, Condé Bénoist Pallen, Thomas Joseph Shahan, John Joseph Wynne, Andrew Alphonsus MacErlean , The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church, Volume 8 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, ©1912) 178-179

[26] Constitución política de la Monarquía Española, Promulgada en Cádiz a 19 de Marzo de 1812

[27] del Moral Ruiz, Joaquín; Ruiz, Juan Pro; Bilbao, Fernando Suárez, Estado y territorio en España, 1820-1930: la formación del paisaje nacional, (Los Libros de la Catarata, ©2007) 25-26

[28] Fletcher, Richard A., The Quest for El Cid (Oxford University Press, ©1989) 50

[29] Kendrick, Thomas Downing, St. James in Spain, (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, ©1960) 21-24

[30] Cantar de Mío Cid, 1.36

[31] Cantar de Mío Cid, 2.95

[32] Fletcher, 55

[33] Castro, Américo, The Spaniards: An Introduction to Their History, (University of California Press, ©1981) 480-81

[34] Kendrick, 24

[35] María Antonia Sáinz Sastre, La Florida, Siglo XVI: Descubrimiento y Conquista (Spain: Editorial Mapfre, ©1992) 131

[36] Lyone, Eugene, “The Enterprise of Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly Vol. 52, No. 4 (Apr., 1974), pp. 416-17

[37] Fiske, John, The Writings of John Fiske, Volume III, “The Discovery of America with some accounts of ancient America and the Spanish Conquest,” (Cambridge: Riverside Press, ©1902) 345

[38] Pope Sixtus IV, Exigit Sinceras Devotionis Affectus, November 1, 1478

[39] Mullett, Michael, The Catholic Reformation, (New York: Routledge, ©1999) 74-75

* See Jane E. Mangan’s note to this effect in de Acosta, José, Natural and Moral History of the Indies: Chronicles of the New World Encounter, Mangan, Jane E., (ed.), López-Morillas, Frances, (trans.) (Duke University Press, ©2002) 1

[40] Gaustad, Edwin Scott and Noll, Mark A., A Documentary History of Religion in America: To 1877 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, ©2003)28-29

[41] Mallios, Seth, The Deadly Politics of Giving: Exchange And Violence at Ajacan, Roanoke, And Jamestown (University of Alabama Press, ©2006) pp. 53–57.

Follow

Follow

Tim, God’s blessings on the new film. Thank God for the memory of the Huguenots.

Tim,

You wrote:

“It is notable that although King Philip II was a patron of the Jesuits, he was not originally eager to send them to the New World for fear of imposing on the Dominicans, Franciscans and Augustinians already present in Mexico and the southern continent.* Menéndez, after removing the Huguenot threat, appealed emphatically to the King to send Jesuits to convert the Indians, complaining that so much could be accomplished if the Jesuits would only come.[40] When the Jesuits finally came and encountered violent resistance to their overtures, Menéndez planned and executed a mission of reprisal to punish the Indians for what they had done to the Jesuits.[41] Thus did the Reconquista come to the New World—on the ships of Menéndez, the man of Asturias, “the last of the crusaders.”

This is the most compelling part. I really believe that this Jesuit group is among the most sinister and evil organizations ever to be created in the world. While our modern ISIS Islamic evil is broadening its operations throughout the middle east, Europe and soon America, there is no other organization in the history of the world than the Jesuits who are responsible for more soul murder and killing of men, women and children to honor the Pope and the Romish church.

People simply have grasped how evil this group is in the history of the world, and it is only getting worse with the global soul murder being promoted by Roman Catholicism.

The head of the Jesuits is called the black pope.

Tim.

Sounds like “Black legend” stuff.

Anyway, the guy couldn’t have been all bad if, “16 people were spared: women, infants, and children under fifteen years of age, as well as anyone who would acknowledge that he was Catholic.”

Jim wrote:

“Tim.

Sounds like “Black legend” stuff.

Anyway, the guy couldn’t have been all bad if, “16 people were spared: women, infants, and children under fifteen years of age, as well as anyone who would acknowledge that he was Catholic.”

What a seriously and incredibly nasty comment that is typical of the Roman Catholic who defends sin and murder at all costs! Jim, you really need to beg the Lord for a saving knowledge of Christ and withdraw from that Romish whore who has totally indoctrinated you with her evil that you call is good.

The Jesuits are the core defenders of soul murder of millions of pour, ignorant Catholics who will ultimately end in everlasting torment. While perhaps you are not a Jesuit who has taken the oath to protect everything the Pope does or says, I can see without the oath you have continued to adopt the same tactics over and over used by this organization.

Growing up Catholic I was taught the Jesuits were the best of the best in the Romish church. It was not until I began to learn the history that I could not in good conscience adhere to anything they practice or promote in their global organization.

I recommend you stop defending evil and wickedness out of your self denial and self responsibility, and start to change your life and withdraw from further promotion of sin.

Tim,

This piece is dumber than the Fenelon one. Have you shot your wad and now must scour every nook and cranny of history of dredge up something to write about? What happened to your Revelation silliness?

You know, you could do a feature on Al Capone. He was a Catholic.

Jim, you may be right. “French Colonial Florida” may indeed be dumbest thing I’ve ever written. In fact, I may be a pathetic blogger writing weekly posts in his pajamas from his mother’s basement, unable to rub two books together to form an idea. That is always one possibility.

On the other hand…

Thanks,

Tim

PS: you may gather from this, and from various other comments from me, that I care very little how I am judged by men or by history. There is a lot of freedom in that.

As you have already discovered, you should pay no attention to “Jim” (aka “Guy” on the Beggars All blog). You provided 41 citations to your sources, but to Jim it’s still “Black Legend Stuff”.

Quite right!

Thanks,

Tim

Tim, I believe Walt left a link here before that I wanted to invite all your Catholic readers to listen to. John MacArthur ” Is Roman Catholicism a false gospel” Its quite good, on youtube. K P. S. Obscure stories like la Florida which have been overlooked by history are packed with so much Tim. Thanks for taking the time to put this out. I personally think the dumbest thing ever written is that a man who called himself a fellow elder, who wrote ” you also” are the royal priesthood” of the saints”, who when Paul was in Rome in 54 A.D. and wrote to the Roman church, never mentions Pope Peter, and who wrote in 62 A.D. 4 other Epistles from jail and never mentions a Pope Peter. That hoax is the dumbest thing written. Hope all is well.

Tim, have you reas an article by Carl Truman ” Pay no attention to the man behindvthe curtain”?

EA,

Do you ever have anything of your own to add to the discussion? It seems you are like a jackal or hyena or some other type of scavenger that follows behind the lion looking for scraps .

You are a heckler that doesn’t get in the fray.

As for Tim, he already has a lap dog. The position is filled. Go back to butt-kissing Steve on the other blog.

“”You are a heckler that doesn’t get in the fray.”

Like categorizing posts as dumb? Yes, quite a contribution, I stand in awe.

EA, I am shocked. You actually made a real comment of your own over on Swanee’s. It’s a first.

EA, Jim is a legend in his own mind.

On its Timucuan Ecological & Historic Preserve site, the National Park Service states, “The settlement barely survived that first year. Good relations with the Indians eventually soured and by the following spring the colonists were close to starvation.” (https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/foca_end_colony.htm, accessed 5/24/2018). Another page on this site states, “The French, well aware of [the Timucuans’] minority status, initially made every effort to avoid alienating local tribes. Only when starvation threatened did this policy unravel. Mistrust turned to armed conflict, and the brief period of harmony between French and Indian came to an end. Yet the Timucuans apparently remained neutral during the attack by the Spanish against the French fort in 1565 and actively assisted De Gourgues’s forces in the successful French recapture of the fort in 1568.” (https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/timucua_end_culture.htm, accessed 5/24/2018.) Your article and the documentary do not mention the deterioration of relations betwixt the French and Indians. Do the primary sources indicate this difficulty?

The documentary mentioned that the natives had created a shrine around Ribault’s monument. (http://aperio.tv/, Part Two, 7:58-8:08). Do primary sources indicate an explanation for why the Indians did this?

Thanks!

Thank you, Carolyn. Great question. Let me look at Ribault’s recollections and see what I can find.

Tim

Thank you, Mr. Kauffman. I look forward to knowing what a primary source said.