Within the library of apocalyptic literature, Daniel’s visions certainly occupy a shelf of their own. And yet his visions could conceivably be further subdivided into three different genres: the Dynastic, the Mosaic, and the Cardinal. Such a distinction between the three types of Daniel’s visions makes chapter 11 stand out in stark relief compared to the others, both in style and in content. When the unique aspects of the chapter are so recognized, chapter 11 is shown to be a continuous, uninterrupted narrative that was entirely fulfilled during the period of Greek rule that is signified by the Bronze, Leopard and He-goat periods of Daniel’s other visions.

The Dynastic Visions—chapters 2, 7, and 8—speak primarily of the succession of world dynasties. The Gold phase of Nebuchadnezzar’s statue in Daniel 2 signifies the Babylonian dynasty, the Silver phase the Medo-Persian dynasty, the Bronze the Greek, the Iron the Roman dynasty in ascent, and the Iron & Clay the Roman dynasty in descent. We can say as much of Daniel 7. The Lion signifies the Babylonian dynasty, the Bear the Medo-Persian dynasty, the Leopard the Greek, and fourth beast the Roman. Daniel 8 narrows the focus to just two dynasties, but in that chapter the Ram signifies the Medo-Persian dynasty and the He-goat signifies the Greek. All three chapters depict the rise and succession of dynasties, and we categorize them in the Dynastic genre.

The vision of Daniel 9, on the other hand, is clearly Mosaic in nature, making no reference at all to dynastic succession, even though the prophecy in its fulfillment spans several dynasties. Daniel had been reading about the seventy year chastisement according to Jeremiah (Daniel 9:2) who himself had reported the words of the Lord: “therefore I will bring upon them all the words of this covenant” (Jeremiah 11:8). When Daniel speaks of the chastisement, he explains that it was Mosaic in nature, because of “the oath that is written in the law of Moses” (Daniel 9:11). When Gabriel speaks of the seven-fold multiplication of the chastisement (Daniel 9:24), he explains that further “desolations are determined” (Daniel 9:26), a reference to Leviticus 26, the only place in the Mosaic Law that prescribes seven-fold punishments and “desolations” for Israel’s continued disobedience. Then when Gabriel speaks of the fulfillment of the Seventy Weeks, the culmination involves the anointing of the Most Holy, which is explicitly prescribed by the Law of Moses for the setting up of the tabernacle (Exodus 40), and which was fulfilled in the restoration of “the law of the house” (Ezekiel 43:12), as we showed in All the Evenings and Mornings. Thus we categorize the 9th chapter of Daniel in the Mosaic genre of Danielic apocalyptic literature.

The vision of chapter 11 is in a completely different genre altogether. It deals with the succession of kings and kingdoms, setting it apart from the vision of chapter 9, but it deals with those kings and kingdoms in a way that is vastly different from the dynastic succession depicted in Daniel chapters 2, 7 and 8. Although on the surface the vision appears almost as a recapitulation of Daniel 8—the fall of the Medo-Persian empire and the rise of the Greek—there is a signifiant difference that cannot escape notice.

Instead of introducing animals or minerals symbolically, and then explaining their symbolic significance (as in the Dynastic visions), the narrator of this chapter simply identifies the period of transition at the outset—from that of Medo-Persian dominance to that of Greek dominance—and then proceeds into a detailed narrative of a history that is yet future to Daniel. The chapter is written “in the first year of Darius the Mede” (Daniel 11:1), after which “there shall stand up yet three kings in Persia” (Daniel 11:2). Then there shall arise “a mighty king” (Daniel 11:3) from “the realm of Grecia” (Daniel 11:2). That “mighty king” is Alexander the Great, and as in Daniel 7:6, 8:8 and 8:22, “four kingdoms shall stand up out of the nation,” and those four shall be distributed “toward the four winds of heaven” (Daniel 11:4).

From that point forward to the end of the chapter there is perpetual conflict among the kings, but there is no further discussion of Medo-Persia or Greece or any named dynasty at all. There is only a discussion of the resulting kingdoms, but no mention of their nationalities. The only identifying attribute we have is each kingdom’s geographic position relative to the others. Their interactions are simply described in terms of the cardinal directions—North (vv. 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, 40, 44), South (vv. 5, 6, 9, 11, 14, 15, 25, 29, 40) and East (vv. 9, 44). Thus we categorize the 11th chapter of Daniel in the Cardinal genre of Danielic apocalyptic literature. It is neither the succession of Dynasties nor the Law of Moses that provides the backdrop, but the points of the compass.

What makes the chapter challenging is that the nations and boundaries of the warring kings are clearly important to our understanding of the fulfillment, but they are never explicitly described. Throughout chapter 11, the angel refers repeatedly and explicitly to countries, regions, territories, cities and other locations with varying levels of geographic specificity: Media (v. 1), Persia (v. 2), Greece (v. 2), Egypt (vv. 8, 42, 43), Israel (i.e., the glorious land, vv. 16, 41, 20, cf. Ezekiel 20:15), the Greek Isles (v. 18), Chittim (v. 30), Edom, Moab and Ammon (v. 41), Libya, (v. 43), Ethiopia (v. 43), and the temple mount (v. 45). Yet despite the extensive use of specific geographic designations throughout the chapter, the angelic narrator nonetheless refrains from referring to the territories of the warring kings except by the cardinal directions, north and south.

Then at verse 44, one of the kings receives unwelcome news, and again, even though the narrator had been so free in his explicit geographic references elsewhere in the vision—i.e., one king’s booty will be carried into Egypt (v. 8), a ship will intervene from Chittim (v. 30), and desirable goods come from Egypt (v. 43)—the angel still will not state the specific origins of the tidings, except that they come from the north and from the east.

All manner of nationality and geography is used freely to describe everything else in the chapter, but the narrator will not divulge that information about the scrimmaging kings or the unwelcome news of 11:44. The angel was clearly authorized to name many nations and locations with considerable geographic precision, except for the territories and nationalities of the warring kings and the origin of the tidings. From this injunction he does not waver.

Despite this, historians and eschatologists have almost universally concluded—and we agree with them on this point—that the bulk of the chapter deals largely with the century of conflict known as the Syrian Wars, the conflict that raged between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties from 274 to 168 B.C..

But the prophecy was too accurate, so to speak, and that has been problematic for some. It is so accurate in its details that liberal theologians have assumed that chapter 11 must have been written after the fact (see John J. Collins, Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature (Eerdmans, 1984)), and secular historians have simply used the chapter as a history book (see Edwyn Robert Bevan, The House of Seleucus, vol 1 (London, 1902)). No prophecy so specific could possibly have been written in advance. So they think.

Conservative theologians—those who understand that the chapter was written as prophecy rather than as history—are presented on the other hand with two problems of a very different nature.

The first problem presents itself immediately upon an inspection of the four cardinal directions, and the problem is that Daniel’s compass appears to be broken. In four different places in his visions—7:6, 8:8, 8:22, 11:4—Daniel depicts the four-way division of Alexander’s empire, and twice explains that they are distributed “toward the four winds of heaven.” For reference, here are the four verses that describe the division:

“After this I beheld, and lo another, like a leopard, which had upon the back of it four wings of a fowl; the beast had also four heads; and dominion was given to it.” (Daniel 7:6)

“Therefore the he goat waxed very great: and when he was strong, the great horn was broken; and for it came up four notable ones toward the four winds of heaven.” (Daniel 8:8)

“Now that being broken, whereas four stood up for it, four kingdoms shall stand up out of the nation, but not in his power.” (Daniel 8:22)

“And when he shall stand up, his kingdom shall be broken, and shall be divided toward the four winds of heaven;” (Daniel 11:4a)

We are certainly not left guessing as to the significance of the “four winds of heaven.” The Scriptures are replete with references to them, and it is clear that they refer to the four cardinal directions:

The North Wind: Proverbs 25:23, Ecclesiastes 1:6, Songs 4:16;

The South Wind: Ecclesiastes 1:6, Job 37:17, Psalms 78:26, Luke 12:55, Acts 27:13, 28:13;

The East Wind: Genesis 41:6, 23, 27, Exodus 10:13, 14:21, Job 15:2, 27:21, 38:24, Psalms 48:7, 78:26, Isaiah 27:8, Jeremiah 18:17, Ezekiel 17:10, 19:12, 27:26, Hosea 12:1, 13:15, Jonah 4:8, Habbukuk 1:9;

The West Wind: Exodus 10:19

Thus, the phrase “toward the four winds of heaven” clearly means toward the North, South, East and West, and as we described in Reduction of the Diadochi, if a compass rose is superimposed upon Alexander’s dominions, the remnants of his empire are plainly distributed in this way. Lysimachus took the North, occupying Thrace and Asia Minor within the Taurus Mountains; Ptolemy and his descendants became the new Pharoahs of Egypt to the South, Seleucus and his descendants took the East from the Taurus mountains to Babylon and beyond, and Demetrius and his descendants took Macedonia to the West.

But the bulk of Daniel 11 (vv. 5-45) describes a series of conflicts between “the king of the north” and “the king of the south,” and this is where the first puzzle lies. The historical evidence suggests, and the commentaries largely agree, that the prophecies in the chapter were fulfilled by a series of wars between the kingdoms of Syria to the east and Egypt to the south. In other words, the prophecy of a sustained conflict between the Northern Kingdom and the Southern Kingdom appears to have been fulfilled by a series of wars between the Eastern Kingdom and the Southern Kingdom. Ought Daniel to have prophesied instead of a conflict between the King of the East and the King of the South? What to do?

The apparent inconsistency traditionally has been resolved by assuming that the frame of reference changed from one centered on Alexander’s empire at 11:4 to one centered on Judæa at 11:5. In the Alexandrian Frame of Reference, Asia Minor is to the north and Egypt is to the south, but from a Judæan Frame of Reference—Syria is north and Egypt is south. Thus those writers who address the Syrian-Egyptian wars in the context of Daniel’s vision typically consider Syria to be the northern kingdom in the Judæan Frame—even though Asia Minor is freely acknowledged to be the northern kingdom in the Alexandrian Frame in the previous verse. Thus, the frame of reference is changed at 11:5, and by this means, most of the text of Daniel 11 has been made to align with the historical record.

This solution, however, has led to some rather creative cartography. Although every writer of note who addresses the puzzle approaches it in largely the same way, we believe Calvin’s attempt provides the most poignant illustration of just how much we must strain at the compass in order to make the prophecy fit the history. Calvin invokes an Alexandrian Frame of Reference at Daniel 8:8, which describes four notable horns distributed “toward the four winds of heaven.” Of this passage, Calvin writes,

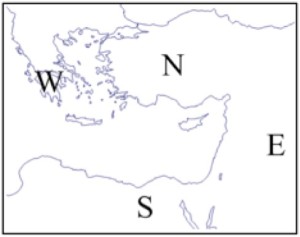

“He says, by the four winds of heaven, that is, of the atmosphere. Now the kingdom of Macedon was very far distant from Syria; Asia was in the midst, and Egypt lay to the south. Thus, the he-goat, as we saw before, reigned throughout the four quarters of the globe; since Egypt, as we have said, was situated towards the south; but the kingdom of Persia, which was possessed by Seleucus, was towards the east and united with Syria; the kingdom of Asia was to the north, and that of Macedon to the west, as we formerly saw the he-goat setting out from the west.” (Calvin, Commentary on Daniel, 8:8; see Figure 1 ,below)

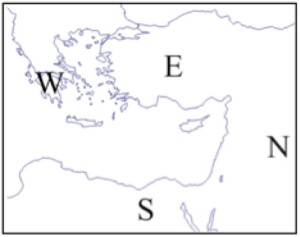

But when commenting on Daniel 11:4, Calvin changes to a Judæan Frame of Reference. At this point, Calvin simply rearranges the four points of the compass to fit the outcome of the prophecy. He writes,

“His empire shall be broken, and shall be divided, says he, towards the four winds of heaven. … Seleucus obtained Syria, to whom his son Antiochus succeeded; Antigonus became prefect of Asia Minor; Cassander, the father of Antipater, seized the kingdom of Macedon for himself; Ptolemy, the son of Lagus, who had been a common soldier, possessed Egypt. These are the four kingdoms of which the angel now treats. For Egypt was situated to the south of Judea, and Syria to the north, as we shall afterwards have occasion to observe. Macedonia came afterwards, and then Asia Minor, both east and west.” (Calvin, Commentary on Daniel, 11:4; see Figure 2, below)

Although his interpretation is strained, to say the least, we must add in Calvin’s defense that the shifting frame has been almost universally reflected in the commentaries since the church first began to expound upon the prophecies. Hippolytus (170 – 235 A.D.), was the first to attempt to identify all four of the Diadochi (Hippolytus, Exegetical Fragments, Third Fragment, Scholia on Daniel, 7:6), the first to suggest “the four winds” as a reference to the points of the compass (i.e., “created existence in its fourfold division” (Hippolytus, Exegetical Fragments, Third Fragment, Scholia on Daniel, 7:2), and the first to suggest a shift from an Alexandrian to a Judæan Frame of Reference at 11:5,

“For thus saith the Scripture: ‘And the king of the South shall stand up against the king of the North, and her seed shall stand up against him.’ And what seed but Ptolemy, who made war with Antiochus?” (Hippolytus, Exegetical Fragments, Second Fragment, Of the Visions, 34)

Jerome (347 – 420 A.D.), too, following Hippolytus, views Daniel 11:4 in an Alexandrian Frame of reference—”Asia Minor and Pontus and of the other provinces in that whole area, that is, in the north”— and then switches immediately to a Judæan Frame at 11:5, “because Judaea lay in a midway position” between Syria and Egypt (Jerome, Commentary on Daniel, 11:4-5). The reformers, to a man, followed suit, rearranging Daniel’s compass to fit the history that clearly fulfilled the prophecy. But Daniel’s oddly configured compass was not the only puzzle in chapter 11.

The second problem encountered in chapter 11 is that beyond the events described in 11:39, the historical record contains no engagement between Syria and Egypt that matches the description of the hostilities between the kings of the north and south in the following verses. Verses 31-39 deal with events subsequent to Antiochus IV’s pollution of the sanctuary in June of 167 B.C., all of which occurred after his second invasion of Egypt was interrupted by Gaius Popillius Laenas in 168 B.C. (Livius, History of Rome, Book 45, 12; Polybius, The Histories, Fragments of Book XXIX, I.2). Wounded in pride, short on funds and unable to fund his own army, Antiochus’ last known whereabouts were in Persia where he was attempting to rob a temple treasure in Elymais, and then in Babylon where he collapsed in despair at the news of his latest defeats at the hands of the Maccabees (1 Maccabees 3:29-31, 6:1-9). A man in his condition does not mount a third invasion of Egypt “like a whirlwind, with chariots, and with horsemen, and with many ships” (Daniel 11:40). His second invasion of Egypt was his last.

His successors were even less capable of such a feat. After Antiochus IV’s death, Rome despatched an envoy to Syria to “cripple the royal power” by burning Antiochus V’s navy and hamstringing his elephants, all of which Antiochus IV had maintained in contravention of the 188 B.C. Treaty of Apamea:

“Octavius and his colleagues thereupon left, with orders in the first place to burn the decked warships, next to hamstring the elephants, and by every means to cripple the royal power.” (Polybius, Histories, Fragments of Book 31.2.11)

With Syria thus disarmed and reduced to a Roman client state, Daniel’s narrative nevertheless presses on uninterrupted and undeterred, describing a dramatic military engagement that ought to have happened next between the kings of the north and south. In the aftermath, there is ominous news originating from the north and the east, resulting in yet another military engagement as he “go[es] forth with great fury to destroy, and utterly to make away many” (Daniel 11:44). These are things that neither Antiochus IV, nor his successors, could even dream of doing, and there is no record of such a conflict, or such troubling tidings, in the history of the Syrian Wars. What to do?

Various writers have attempted to solve the puzzle in different ways. Porphyry (234 -305 A.D.), writing from a secular perspective, assumed that the author of Daniel had lived at the time of Antiochus IV in the 2nd century B.C.. Porphyry therefore concluded that Antiochus IV must have made a third invasion of Egypt (Jerome, Commentary on Daniel, Prologue, 11:40-45)—an invasion for which there is no evidence in the historical record and which Antiochus IV was hardly equipped to execute. Other historians have simply concluded that Daniel, or the author claiming to be Daniel, was wrong, and that he had merely been guessing at a potential future outcome, one that he could not possibly see in advance.

Conservative theologians, on the other hand—those who understand that the chapter was written as prophecy rather than as history or as fraud—resolve the puzzle in the same way that they resolved the puzzle of 11:5. They simply introduce another frame of reference. This frame is centered neither on Alexander’s empire, nor on Judæa, but rather on the person of a future antagonist. We call it the Eschatological Frame of Reference.

Hippolytus saw the Eschatological Frame introduced as early as 11:31, and identifies the antagonist as a Latin Antichrist, whom he has in possession of Egypt, Libya and Ethiopia (Hippolytus, Exegetical Fragments, Second Fragment, Of the Visions, 40; Third Fragment, Scholia on Daniel, 12:11). The unwelcome tidings come from the northeast of his geographic location in North Africa, and therefore his response to the tidings is to go out with fury toward Tyre and Beirut (Hippolytus, Treatise On Christ and Antichrist, 52).

Lactantius (250 – 325 A.D.) understood a transition to an Eschatological frame no later than 11:35, and saw the antagonist coming from the northern territories into Syria, which he has toward the east (Lactantius, Book VII, chapter 17). He does not address the origin of the tidings of 11:44.

Victorinus (c. 310) touches only tangentially on the Diadochi, and understood the Eschatological Frame to begin no later than 11:37 (Victorinus, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 17), seeing it in the context of the beast and the harlot of Revelation 13 and 17, and identifying Antichrist as Imperial Rome, or Nero (Victorinus, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 7, 12, 17). He provides no indication of Antichrist’s location prior to placing “his temple within Samaria” at 11:45 (Victorinus, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 13, 17), and does not address the origin of the tidings of 11:44.

Jerome saw the transition to the Eschatological Frame as early as 11:24:

“the rest of the text from here on to the end of the book … those of our persuasion believe all these things are spoken prophetically of the Antichrist.” (Jerome, Commentary on Daniel, 11:24)

At 11:43, he has Antichrist in possession of Egypt, Libya and Ethiopia. Then Antichrist “is going to hear that war has been stirred up against him in the regions of the North and East,” which therefore has him pitching his tent “in the province of Judaea.”Jerome does not provide any specific point of origin in the north and east. He simply notes that the rumors cause Antichrist to leave his holdings in North Africa and settle in Judæa, which suggests that he saw Israel as the origin of the rumors, north and east of Egypt, Libya and Ethiopia (Jerome, Commentary on Daniel, 11:40-45).

The reformers, too, were all over the map. Broughton and Willet maintained a Judæan frame of reference to the end, thinking that 11:40-45 must refer to Antiochus IV. Œcolampadius, Bullinger, Polanus and Mayer saw a transition to the Eschatological Frame at 11:21, Melanchthon at 11:32, Calvin and Wigand at 11:36, Calvin seeing the events fulfilled near-term by imperial Rome (references below). Luther saw the transition to the Eschatological Frame taking place at 11:40, and cut short his commentary at Daniel 11:39, “for only in experience can this chapter be understood and Antiochus spiritually discerned” (Luther, Preface to the Prophet Daniel). Among these reformers, several allowed for a double fulfillment, the first by Antiochus IV, and the second by the Turks or Papal Rome.

Calvin, although he disagrees with the rest on the fulfillment, nevertheless typifies their confusion as he plods through the events of Daniel 11. As late as 11:27, Calvin had been marveling at the precision and accuracy of the prophecies which “are so clearly pointed out … when the angel predicts the future so exactly, and so openly narrates it, as if a matter of history” (Calvin, Commentary on Daniel, 11:27). But by 11:40, he has resigned himself to the obsurity of the passage, throwing up his hands in defeat. Here he assumes that the narrator of chapter 11 had set aside continuity and clarity, and left us with a prophecy in which the main players are so confused that we can no longer tell them apart, or even know the exact fulfillment of the prophecy:

“I dare not fix the precise time intended by the angel. … The angel did not propose to mark a continued series of times … Whatever be the precise meaning … sometimes events were so confused that the Egyptians coalesced with the Syrians, and then we must read the words conjointly … Nor is it necessary here to indicate the precise period, since the Romans carried on many wars in the east.” (Calvin, Commentary on Daniel, 11:40)

There are many other such similar examples as these attempts to grapple with the puzzles of chapter 11. To solve the curious inconsistencies—that is, Daniel’s “compass problem” and the fact that at some unspecified point in the narrative he simply departs from continuous history without warning, launching into the fog of some even more distant future past—the solution has been to impose new frames of reference upon the text. Daniel 11:4 is largely and naturally taken to be written in the Alexandrian Frame, but then without notice 11:5 is assumed to be the beginning of a narrative written in the Judæan Frame. Then at some later unspecified point, the narrative switches, again without notice, to an Eschatological Frame in which the cardinal directions are relative to the geographic location of Antiochus IV or some other future antagonist.

The result of this approach, of course, has been absolute chaos. One writer centers the Eschatological Frame of Daniel 11 on Rome, and the unwelcome tidings come from Germany to the north and Constantinople to the east. Another has them coming from Bulgaria and England. The Pope, after all, resides “between the seas” (Daniel 11:45) of the Adriatic and the Tyrrhenian. Or perhaps the Eschatological Frame may be centered on the Turks, with the tidings originating from north and east of Istanbul, which resides between the Aegean and the Euxine. Others have the frame of reference set from the perspective of Antichrist in North Africa, and the tidings originate from Jerusalem, north and east of him. Still others, keeping Antiochus in view, have the final reference frame set in Judea, and Antiochus hearing unwelcome news from Syria to the north and from Persia to the east. Another writer reverses even these, having the tidings originate from Persia to the north and Syria to the east. One writer keeps the reference frames consistent from 11:5 to 11:40, and another warns that we should not do so, lest we hold too strictly to the literal sense and miss the prophetic sense (Œcolampadius, 150r). When the frames of reference change from writer to writer, and even from chapter to chapter within a single writer—Melanchthon proposes as many as five centered on Alexander, Judæa, Antiochus IV, Papal Rome and the Turks—it is impossible to elicit from them a common understanding of the relative geographic positions intended by North, South and East. There is simply no consensus to be found.

And yet, in spite of this confusion, the shifting of the frame—from an Alexandrian Frame at 11:4 to a Judæan Frame at 11:5 to an Eschatological Frame at some point after that—has been so universally applied in the history of Danielic eschatology that it has become well nigh canonical. The shifting frame is tacitly assumed to be a part of the canon of revelation itself. Upon inspection, however, there is not so much as a whisper of a hint of a suggestion in the text of Daniel 11 that the frame of reference had changed at all. An Alexandrian Frame was established as early as Daniel 8:8, and is restated for us at 11:4, “toward the four winds of heaven,” and the narrator never departs from it. It is in the context of this Alexandrian Frame of Reference that the narrator proceeds into a detailed description of events with respect to the compass points—north, south and east—as those events unfold within a single frame of reference, all the way through Daniel 11:45.

What the Early Church Fathers and the reformers—and modern commentators with them—apparently did not consider is the possibility that all of Daniel 11 is to be read continuously in one, single Alexandrian Frame of Reference in which North refers to Asia Minor, from start to finish. Perhaps the chaotic jumble of interpretations at the Eschatological Frame is actually caused by the fact that we introduced a Judæan Frame at 11:5 in the first place.

And thus we ask, What if Daniel’s compass was not broken at all? What if North meant North?

We will continue on this theme in our next entry.

________________________________

Notes:

Reformers on the transition to an Eschatological Frame: Oecolampadius, Johannes, In Danielem Prophetam (Basileae: Apud Thomas Volfius (1530)) 140r-140v, 147v, 150r; Calvin, John Commentary on Daniel, 11:36; Bullinger, Heinrich, Daniel Sapientissimus Dei Propheta, (Tiguri Excudebat C. Froschoverus, 1565) 124r; Melanchthon, Philipp, In Danielem Prophetam Commentarius, (Lipsiæ (1543)), 360-362; Wigand, Johann, Danielis Prophetae Explicatio Brevis, (Jena, Berlin: Guntherus Huttichius ex. cudebat. 1571) , 425r-426v; Broughtono, Hughone, Commentarius in Danielem, (Basileæ per Sebastianum Henricpetri (1599)) 84; Polandi, Amani, In Danielem Prophetam Visionum, vol. ii (Basileæ, Typis Conradi Waldkierchii (1599)) 316-18; Willet, Andrew, Hexapla in Danielem (Cambridge: Leonard Greene (1610)), 435; Mayer, John, A Commentary Upon the Whole Old Testament, vol 4 Upon all the Prophets both great and small (London: Robert & William Laybourn 1653) , 574

Follow

Follow

ELLIOTT, E.B.

Horae Apocalypticae; or, A Commentary on the Apocalypse, Critical and Historical; Including Also An Examination of the Chief Prophecies of Daniel. Illustrated by an Apocalyptic Chart, and Engravings from Medals and Other Extant Monuments of Antiquity. With Appendices: Containing, Besides Other matters, A Sketch of the History of Apocalyptic Interpretation, Critical Reviews of the Chief Apocalyptic Counter-Schemes, and Indices. (4 volumes, 1862)

All the major Reformers and all the major Reformation creeds and confessions adopted the historicist position — and it is this position that Elliott so skillfully defends. Included in Horae Apocalypticae you will also find a very useful historical survey of who held which positions concerning eschatology, much history on the Roman empire (and its interaction with Christianity), how the Reformation, Islam, etc., were prophesied in the Apocalypse, a world chronology according to the Hebrew Scriptures (which would make the Earth 6127 years old), patristic views of prophecy, the beast and his mark (666) revealed, and much more. The Papacy is also shown to be the apocalyptic antichrist, which was a standard position among the Reformers. Elliott also deals with Moses Stuart’s Preterism.

Concerning Elliott’s Horae Apocalypticae H. Gratton Guinness, writes, “The ‘Horae Apocalypticae’ of Elliott, which may well be considered as the most important and valuable commentary of the Apocalypse which has ever been written, was also called into existence by Futurist attacks on the Protestant interpretation of prophecy (and the same would apply in our day, but even more so, as the classic Protestant system of interpretation for the book of Revelation is still being undermined by the Jesuit inspired Futurist system, but also, increasingly [even in so-called “Reformed” circles] by the other Jesuit inspired system: Preterism!–RB).”

“His Horae Apocalypticae (Hours with the Apocalypse) [literally ‘time with the Apocalypse’] is doubtless the most elaborate work ever produced on the Apocalypse… Begun in 1837, its 2500 pages of often involved and overloaded text are buttressed by some 10,000 invaluable references to ancient and modern works bearing on the topics under discussion…. Perhaps its most unique feature is the concluding sketch of the rise and spread of the Jesuit counter systems of interpretation that had made such inroads upon Protestantism” (http://www.historicist.com/horae.htm).

“When he (Spurgeon–ed.) reaches the book of Revelation his clear recommendation is E.B. Elliott’s Horae Apocalypticae. He succinctly states that it was “the standard work”. It would surprise most Baptists today to realize that this most eminent Baptist preacher was himself an Historicist or Continuist as he called it then. Elliott’s work was the standard work in 1878 because the Historicist interpretation was still the standard in Protestantism and this work had gone through 4 editions and had established itself as the standard within the Historicist school” (http://www.historicist.com).

2611 pages, with a 29 page index.

M’LEOD, ALEXANDER

Lectures Upon the Principal Prophecies of the Revelation (1814)

David Steele writes, “I can again cordially recommend to his attention the Lectures of Doctor M’Leod, as the best exposition of those parts of the Apocalypse of which he treats, that has come under my notice.”

DURHAM, JAMES

A Complete Commentary Upon the Book of Revelation (1658, 1799 edition, 2 volumes)

“After all that has been written it would not be easy to find a more sensible and instructive work than this old-fashioned exposition… the mystery of the Gospel fills it with sweet savour” writes Spurgeon of this work (cited in Johnston, Treasury of the Scottish Covenant, p. 318, emphasis added).

STEELE, DAVID

Notes on the Apocalypse (1870)

Brooks says, “I have derived more knowledge of the Apocalypse from this work than from all other expositions which I have consulted.”

STEELE, DAVID

The Two Witnesses: Their Cause, Number, Character, Furniture and Special Work (1859)

This is a great companion volume to Steele’s Notes on the Apocalypse (above). Here Steele zeros in on and works primarily from the text of Revelation 11:13, “I will give power unto my two witnesses, and they shall prophecy.” Steele deals with testimony-bearing, Antichrist, Popery, the beasts of Revelation, the mark of the beast, 666, the image of the beast, civil and ecclesiastical apostasy, Reformation, covenanting, heresy, schism, terms of communion, slavery, sectarianism, Mormonism, Independency, freemasonry, history, worship, idolatry, Britain, the United States, Canada, mystical Babylon, the last days, the ultimate victory of the church and a host of other subjects!

FABER, GEORGE S.

A Dissertation on the Prophecies, That Have Been Fulfilled, Are Now Fulfilling, or Will Hereafter Be Fulfilled Relative to the Great Period of 1260 Years; The Papal and Mohammedan Apostacies; The Tyrannical Reign of Antichrist, or the Infidel Power; and the Restoration of the Jews (2 volumes, 1811)

Understanding the Reformation position on eschatology, as it is set forth in this work, gives us great insight into why the Romanists (i.e. the Jesuits in particular) were so intent on planting both Preterism (Alcasar, c. 1615) and Futurism (Ribera, c. 1585) among the Protestants. 583 pages.

NEWTON, ISAAC

Observations Upon the Prophecies of Daniel (1831)

NEWTON, THOMAS

Dissertations on the Prophecies Which Have Remarkably Been Fulfilled, and at this Time are Fulfilling in the World (2 volumes, 1817)

The author defends the historicist position of eschatology. Historicism teaches that a number of the prophecies of Scripture, and especially those in the book of Revelation, will be seen to be fulfilled throughout history. The specific prophetic fulfillments in question (for example what does the “beast” or “the mother of harlots” in Revelation 17 refer to?) are not seen to be past (as in the Preterist system) or future (as in the Futurist system); neither are they spiritualized to refer to general ideas (of good versus evil) without specific historic fulfillment (as in the Typico-Spiritual system). The historicist position was ensconced in all the substantial Reformed confessions (including the preamble to the Decrees of Dort [1618-19] and the Westminster Confession of Faith [1647]); and no major Reformed Confession has ever taken the Preterist or Futurist position (which is not surprising, since both of these positions, as systems, originated with the Jesuits). Historicism was the position held by almost all the Reformers including Luther, Calvin and Knox. This book also covers the whole book of Revelation. Twelfth edition, indexed, 439 (vol. 1) and 440 pages (vol. 2).

Hi, Walt,

Can you elaborate on your point? I understand you have great respect for Elliott’s Horæ Apocalypticæ. Elliott writes on Daniel 8:8,

Then, in Daniel 11, he writes,

So here Elliott essentially lays out the three-frame system of Daniel 11—an Alexandrian Frame, in which Asia Minor is north, a Judæan Frame in which Syria is North, and an Acpocalyptic Frame in which “north” is relative to the geographic location of a future antagonist, perhaps papal Rome or the Turks.

By providing this litany of praise of Horæ Apocalypticæ, was it your intent to document that fact that church has already received the true interpretation of Daniel 11 under the traditional rubric of the shifting frame? Or was it your intent to show how universally the three-frame system has been adopted?

Thanks. I just wasn’t sure what you meant by the comment.

Tim

Tim wrote:

“By providing this litany of praise of Horæ Apocalypticæ, was it your intent to document that fact that church has already received the true interpretation of Daniel 11 under the traditional rubric of the shifting frame? Or was it your intent to show how universally the three-frame system has been adopted?”

The purpose was to give your readers more modern references to sources that are more consistently reformed historicist materials, and allow them to source comparisons to your explanation from the best reformed authors in eschatology. While it is great to use the early church fathers, and to reference Calvin and Luther and other pre-reformation authors, I think some of the best literature explaining eschatology comes post Calvin and Luther in the first reformation period, and authors who hold largely to that period of biblical interpretation.

Calvin and Luther had their strengths, but they were both not in eschatology as many in the reformed circles attest. You said:

“What the Early Church Fathers and the reformers—and modern commentators with them—apparently did not consider is the possibility that all of Daniel 11 is to be read continuously in one, single Alexandrian Frame of Reference in which North refers to Asia Minor, from start to finish. Perhaps the chaotic jumble of interpretations at the Eschatological Frame is actually caused by the fact that we introduced a Judæan Frame at 11:5 in the first place.”

When you said “and modern commentators with them”, I did not know who you were talking about so I wanted to give the reader the benefit of these references so they can compare your views to the best reformed writers on eschatology that you have not desired to share in your comparisons.

Thank, Walt. I understand that in other areas, Elliott may have surpassed Luther and Calvin. But in Elliott’s three-frame interpretation of Daniel 11, he offers no significant improvement over Luther and Melanchthon, who both saw the Turks and Papal Rome in their own Eschatological Frame. Elliott does nothing more than assume a change in reference frame without Scriptural warrant, and then proceeds to interpret his assumption. In this, he is no different than the others. If Luther offers a shifting frame of reference in a chapter that makes no suggestion of a change of reference frame, and Melanchthon offers a shifting frame of reference in a chapter that makes no suggestion of a change of reference frame, in what way has Elliott improved on them by offering a shifting frame of reference in a chapter that makes no suggestion of a change of reference frame?

On the shifting frame, Elliott along with the vast majority of Dispensationalists today, as well as the early church fathers and early reformers, offers an extrascriptural shifting frame of reference that is foreign to the text and is in fact nothing but another tradition in a chorus of traditions. Why should Elliott’s tradition be more authoritative and supersede Luther’s, Melanchthon’s, Jerome’s, Victorinus’, Hippolytus’ and Lacantius’? That’s what I’m trying to figure out. As I read Elliott on Daniel 11, he offers no improvement with regard to the frame of reference. What am I missing?

Thanks,

Tim

Tim said:

“What am I missing?”

Let’s wait and see what Jim and Bob say as their weekly posts are really authoritative in regards to these questions. 🙂

I’ve sent emails to two experts in eschatology tonight, and am waiting to get a much more detailed reference on Daniel 11 that I will be able to counter your arguments in time. I’m still waiting weeks for some of your past promises to respond to specific points so likewise be patient with me.

It will take a few more of your posts to fully understand where you are going with this theory, and then we can bring the best reformed tradition forward to dismantle it forever. Until then, I’ll have to leave it up to both Jim and Bob, and the Roman Catholics to dismantle your arguments with their typical smoke and mirror commentary. The reformers are far more detailed in this area of eschatology as they are far more used to interpreting all scripture with scripture rather than taking everything as a literal meaning of every word and text as is so common by those preaching and teaching prophecy.

Thanks, Walt. I look forward to hearing the scriptural argument from the later reformers on why they introduce the Judæan and Eschatological Frame of Reference into a chapter that is written from an Alexandrian Frame alone.

Tim

David Steele writes:

“Daniel was solicitous to “know the truth (interpretation) of the fourth beast, which was diverse from all the others,” (ch. vii. 19.) Although “diverse from all the others” in geographical extent and destructive power, this fourth beast combined in one all the ravenous propensities of the three predecessors, but in reverse order. The “leopard, bear and lion of Daniel,” by which Grecian, Persian and Chaldean dynasties were symbolized, are all comprised in John’s beast of the sea,—the antichristian Roman empire. Since this beast of the sea embodies all the voracious properties of the three persecuting powers which went before it; this may be a suitable place briefly to review the sufferings inflicted by them upon the saints, that we may know what the witnesses were taught to expect at the hands of this monstrous enemy.—“Israel is a scattered sheep, the lions have driven him away: first, the king of Assyria hath devoured him, and last, this Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon hath broken his bones.—The violence done to me and to my flesh, be upon Babylon, shall the inhabitant of Zion say; and, My blood upon the inhabitants of Chaldea, shall Jerusalem say.” (Jer. 1. 17; li. 35.)—“Haman, the son Hammedatha, the Agagite, the Jews’ enemy,—thought scorn to lay hands on Mordecai alone.”—“If it please the king, let it be written that they (the whole people) may be destroyed; and I will pay ten thousand talents of silver,—to bring it into the king’s treasuries.”—“Behold also the gallows, fifty cubits high, which Haman had made for Mordecai, who had spoken good for the king, standeth in the house of Haman. Then the king said, Hang him thereon.” (Esth. iii. 1, 9; vii. 9.) Such were the crimes and such the punishments of the enemies of God’s people in Babylon and Persia, as already matter of inspired history: and had we equally full and authentic records of the punishmentsas we have of the cruelties of Antiochus and other successors of Alexander the Great, the king of Greece, we would see, as in the other cases, “the just reward of the wicked.” Of all these idolatrous, tyrannical and persecuting powers, which the Divine Spirit represented by beasts of prey, it was foretold that they were to be removed in succession and with violence. This fourth beast, “dreadful and terrible and strong exceedingly, was to devour and break in pieces, and stamp the residue with the feet of it.” (Dan. vii. 7.) Moreover, while it is predicted of them that “they had their dominion taken away,” it is also added,—“yet their lives were prolonged for a season and time,” (v. 12.) That is, though their distinct and successive dominions were severally swept from the earth, yet their lives,—the diabolical principles by which they had been actuated survived; and these passed, by a kind of transmigration, into the body of the fourth beast. This transition of animating principles or imperial policy of inveterate hostility to the kingdom of God, we think, is plainly indicated by the three features of this beast of the sea, the “leopard, bear and lion.” If these three “slew their thousands,” this monster has “slain his ten thousands” of the saints; and the remnant of the woman’s seed are yet to be “slain as they were,” (ch. vi. 11.)

“The dragon gave him his power,”—physical force, “his seat” or throne,—his right to reign, “and great authority”—dominion—by the voice of the people. Thus, it is obvious that the seven-headed, ten-horned beast is the first, and the oldest, among the combined enemies of the Christian church; all of whose origin is from the dragon, the abyss or bottomless pit. The writers of the church of Rome, while forced to acknowledge that this beast is emblematical of the Roman empire, still insist that pagan Rome is intended. It is sufficient in opposition to this false interpretation to observe, that the beast appears to John with crowns, not upon his heads, but upon his horns, denoting the actual division of the empire into ten kingdoms: an event which did not transpire till after the empire had become nominally Christian under the reign of Constantine the Great. The reign of this emperor and his successors, by their largesses fostered the luxurious propensities of the Christian ministry, and so contributed to prepare the way for the rise of the next enemy in this antichristian confederacy against the witnesses.—The “head wounded unto death is the sixth. John says expressly, elsewhere, “five are fallen, and one is, and the other is not yet come,” (ch. xvii. 10.) The “five fallen” were, kings, consuls, dictators, decemvirs, and military tribunes. All these forms of civil government had passed before the time of the apostle. The one existing in his time, was the sixth head,—the emperors; by one of whom the apostle was now subjected to banishment in the desert isle of Patmos. This wound is supposed by some to be the change from paganism to Christianity in the empire. No; this view is many ways erroneous: but it is enough to remark that the Roman empire, according to both prophets, Daniel and John, is to continue bestial under all changes, during the whole period of 1260 years. The deadly wound was inflicted by the northern invaders who overturned the empire, and, for the time, extinguished the very name of emperor in the person of Augustulus. After the division of the western member of the empire had been subdivided among the victorious leaders of the invaders from the north, and the people of that section supposed the beast slain, the throne of Constantinople continued to be occupied by the representative of the empire. In the popular apprehension the imperial head of the beast seemed to be utterly cut off by the sword of Odoacer,—“wounded by a sword:” but the several kingdoms into which the empire was divided, in process of time became united in the bonds of an apostate faith. The imperial name and dignity were revived in the person of the emperor of Germany, Charlemagne, in 800; and by the wars among the horns of the beast, the title of emperor has been claimed alternately by Germany, Austria and France, down to our own time. These dissensions and rivalries among the sovereigns of Europe,—the mystic horns of the beast, were foreshadowed in the Babylonish monarch’s dream:—“the kingdom shall be partly strong and partly broken,—they shall not cleave one to another, even as iron is not mixed with clay,” (Dan. ii. 42, 43.) And doubtless these internal commotions among the common enemies of the saints of God, have tended, in divine mercy, to divert their attention occasionally from the witnesses. While they have been made the instruments of mutual punishment, the Lord’s people have been “hid in the day of his fierce anger.” (Zeph. ii. 3.)”

I cannot find references to Daniel 11 in detail here:

http://www.bookrags.com/ebooks/14485/186.html#gsc.tab=0

WALT–

You said: “Let’s wait and see what Jim and Bob say as their weekly posts are really authoritative in regards to these questions. 🙂

Until then, I’ll have to leave it up to both Jim and Bob, and the Roman Catholics to dismantle your arguments with their typical smoke and mirror commentary.”

Well, when you and Tim get it all figgered out on which of your theories is actually the truth, then the rest of the world will commend you for a job well done. They are holding their breath in great anticipation.

I’m sure Tim and Walt will figure it all out and save Christianity. It took God 2,000 years to send them, but who am I to complain. At least all these mysteries will be solved in my lifetime!!!!

Provided you live long enough!

Tim, thx very much for explaining the “compass” issues of other interpretations.

I have not read other literature where N E S or W suddenly change, except sometimes Einstein’s frames of reference get me giddy.

Keeping the directions as per normal makes sense in that God’s Word is not meant to confuse us. Some places are hard to understand, but that does not mean impossible to understand.

Keeping the frames of reference standard seems the best way to read it. We look forward to the rest of your study.