Last week we concluded our analysis of the Council of Sardica in 343 A.D., as well as the correspondence leading up to it. As we noted, the council recognized Roman metropolitanism, but not Roman primacy. It is true that bishop Hosius said that those who choose to appeal in Rome should submit their appeal through Julius, the metropolitan bishop there. But he also said that any metropolitan in any metropolis in any province could handle appeals as well. The venue for appeal was up to the accused (Sardica, Canon 5), “[b]ut those who come to Rome ought” to appeal through Julius in memory of Peter (Sardica, Canon 9). Hosius’ particular reference to Rome was not because of Roman primacy but rather due to the fact that he had been commissioned to review the facts of the case, and the facts of the case included Athanasius’ appeal to Julius in Rome. When the facts of the case were related to an appeal to Alexandria (as in Canon 14), the deposed clergyman was “to take refuge with the bishop of the metropolis” in his province without demanding a resolution “in advance of the decision of his case.” Likewise, the deposing bishop was not to “take it ill that examination of the case be made, and his decision confirmed or revised.” Whether the matter related to Athanasius’ deposition, or Ischyras’ deposition, Constantine’s rules of appeal were to be followed. Instead of advancing the case of Roman primacy, bishop Hosius had rather codified the primacy of the Constantinian appeals process that widely expanded access to justice and minimized direct appeals to the Imperial Court, while keeping his court open as the final venue of appeal. Even the court in Rome was required by Sardica to compile its findings and “send them to the Court” of the Emperor for ratification (Sardica, Canon 9).

It is inconsistent with history and the plain meaning of the canons of Sardica, therefore, to conclude that the Council recognized Rome as a court of last appeal; the canons plainly allowed for appeal to the Imperial Court by any metropolitan as long as the appeal did not undermine the Constantinian appellate reforms, did not unduly burden the Emperor, and did not bring the church into disrepute (Canon 7). It is only when Sardica is extracted from its historical and literary context that it can possibly be construed as assigning judicial and ecclesiastical primacy to Rome and her bishop. Therefore, Roman Catholicism is ever eager to engage in just such a contextual extraction and recast Sardica as if it had decreed Rome and the pope as the final court of appeals in the church.

The revision of the history of the Council of Sardica started early, as seen with the deposition of Apiarius in 418 A.D.. Bishop Urban of Siccas in Egypt had deposed presbyter Apiarius of Tabraca for moral turpitude, and Apiarius immediately appealed to pope Zosimus of Rome. Zosimus just as immediately reversed the decision of Urban upon no examination of the facts of the case. Zosimus then dispatched Bishop Faustinus and two presbyters, Philip and Asellas, from Rome to Carthage to inform the Africans that “bishop Urban should be excommunicated or even sent to Rome, unless he should have corrected what seemed to need correction” (Canon 134, The Code of Canons of the African Church; [Unless otherwise noted, all citations below are from these canons]).

Faustinus took the letter from Zosimus to a synod in Carthage, and as was customary, the Canons of Nicæa were brought forward to be read at the opening session. Daniel the Notary did the honors:

“Daniel the Notary read: The profession of faith or statutes of the Nicene Synod are as follows….” (Introduction)

While Daniel was still speaking, Faustinus interrupted, claiming that he had news from the Pope relating to the Nicæan canons, and that news urgently required the attention of the assembled bishops. Faustinus said,

“There have been entrusted to us by the Apostolic See certain things in writings, and certain other things as in ordinances to be treated of with your blessedness as we have called to memory in the acts above, that is to say, concerning the canons made at Nice, that their decrees and customs be observed … Let, therefore the commonitorium come into the midst, that you may be able to recognize what is contained in it, so that an answer can be given to each point.” (Introduction)

Bishop Aurelius, president of the council, agreed to have the commoniturium brought forward to be read, and Daniel again performed the honors. The commonitorium was a letter from Zosimus to Faustinas and the two presbyters, instructing them to go to Carthage to straighten things out. So that no questions would arise, the canons of Nicæa had been written down for them by Zosimus himself:

“To our brother Faustinus and to our sons, the presbyters Philip and Asellus, [from] Zosimus, the bishop. You well remember that we committed to you certain businesses, and now [we bid you] carry out all things as if we ourselves were there (for), indeed, our presence is there with you; especially since you have this our commandment, and the words of the canons which for greater certainty we have inserted in this our commonitory. For thus said our brethren in the Council of Nicaea when they made these decrees concerning the appeals of bishops:

“Decreed, that if any bishop is accused, and the bishops of the same region assemble and depose him from his office, and he appealing, so to speak, takes refuge with the most blessed bishop of the Roman church, and he be willing to give him a hearing, and think it right to renew the examination of his case, let him be pleased to write to those fellow-bishops who are nearest the province that they may examine the particulars with care and accuracy and give their votes on the matter in accordance with the word of truth. And if any one require that his case be heard yet again, and at his request it seem good to move the bishop of Rome to send presbyters a latere, let it be in the power of that bishop, according as he judges it to be good and decides it to be right—that some be sent to be judges with the bishops and invested with his authority by whom they were sent. And be this also ordained. But if he think that the bishops are sufficient for the examination and decision of the matter let him do what shall seem good in his most prudent judgment.

Ancient epitome: If bishops shall have deposed a bishop, and if he appeal to the Roman bishop, he should be benignantly heard, the Roman bishop writing or ordering.” (Zosimus’ Commonitorium)

Those who have been keeping up with this series will recognize that the canon Zosimus cited was not from the Council of Nicæa in 325 A.D., but from the Council of Sardica in 343 A.D.. That was just one of Zosimus’ errors. There were many more.

Those Sardician decrees had a context, and that context was Constantine’s appellate reforms recently completed in 331 A.D. and adapted by the Church at Sardica in 343 A.D.. The duty of the court of appeals was to conduct an inquiry and let both parties participate in the process until all the evidence was collected for a fair representation of both sides as part of a thorough judicial review. The court was to examine “the particulars with care and accuracy.” The inquiry was to be completed, “not through the interference of the judge, but because of the satisfaction of the litigants” (Dillon, John Noël, The Justice of Constantine: Law, Communication, and Control (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, (2012), 203). Zosimus’ failure even to attempt to examine the facts of the case prior to a ruling was a gross violation of Sardica and of Constantine’s reforms.

The canons of Sardica also required the presiding bishop in a matter of appeal to collect the evidence from both sides in writing and upon a ruling to send full documentation (instructio plena) in a dossier to the Imperial Court for a final judicial review. Zosimus had cited Canon 5 about Athanasius’ particular appeal to Rome, but had ignored Canon 9, which required that the resulting sententiam be sent from the Roman court to the Imperial Court in Ravenna before any sentence could be imposed.

In fact there had been no dossier at all, for Zosimus had flatly ignored the very canons that he was wrongly attributing to Nicæa. Faustinus had arrived in Carthage without any written evidence, either to clear Apiarius or even to show the validity of his appeal. The bishops of Africa “earnestly asked” the Roman delegation “to present it rather in writing,” but all that could be produced was the letter from Zosimus instructing Faustinus to overturn Urban’s decision on threat of excommunication. Absent the required instructio plena, there was no evidence that the appeals process had been followed, and there was no proof of the validity of the sententiam from Zosimus. The noncompliance was grotesque:

“For first he [Faustinus] vehemently opposed the whole assembly, inflicting on us many injuries, under pretence of asserting the privileges of the Roman Church, and wishing that he should be received into communion by us, on the ground that your Holiness, believing him to have appealed, though unable to prove it, had restored him to communion.” (Canon 138, Epistle of the African synod to Pope Celestine)

What is more, Canon 5 of Sardica, as the Africans well knew, applied only if a deposed bishop sought refuge in Rome. But Apiarius was not a deposed bishop. He was a deposed presbyter, a matter that was to be addressed by Canon 14. If the Canons of Sardica were to be read as written, Apiarius should have taken his appeal to Cyril, the metropolitan of Alexandria, for that is what Canon 14 of Sardica explicitly prescribed for a deposed presbyter:

“Let him that is cast out be authorized to take refuge with the bishop of the metropolis of the same province. And if the bishop of the metropolis is absent, let him hasten to the bishop that is nearest, and ask to have his case carefully examined.” (Sardica, Canon 14)

In fact, the assembled bishops in Carthage invoked that very canon, in objection to Zosiumus’ demands, recalling that there had been “something about presbyters and deacons” in the canons. Aurelius instructed Notary Daniel to find the canon about deposed presbyters in the commonitory, and Canon 14 of Sardica was brought forward to be read.

The bishops knew quite well that the appellate process had been and was being violated by Zosimus. There was a process to be followed. Apiarius had violated it and Zosimus was complicit in the violation by advancing his appeal. By the language of Canon 14, Apiarius was explicitly commanded by Sardica not to demand communion in advance of a ruling from Alexandria, and Zosimus was explicitly forbidden by the same canon from granting it to him outside of the appeals process:

“But until all the particulars have been examined with care and fidelity, he who is excluded from communion ought not to demand communion in advance of the decision of his case.” (Sardica, Canon 14)

Additionally, according to Canon 9, if Apiarius disagreed with the outcome of that decision, he could just as well have requested an appeal through the bishop of Ravenna, where Emperor Honorius had set up his residence and was currently “administering public affairs.” By Canon 9, it was in fact the duty of Cyril, the metropolitan of Alexandria, to tender a petition to the Emperor upon the request of the accused:

“[I]f in any province whatever, bishops send petitions to one of their brothers and fellow-bishops, he that is in the largest city, that is, the metropolis, should himself send his deacon and the petitions, providing him also with letters commendatory, writing also of course in succession to our brethren and fellow-bishops, if any of them should be staying at that time in the places or cities in which the most pious Emperor is administering public affairs.” (Sardica, Canon 9)

We must keep in mind that the context of the canons of Sardica was that of correctly appealing to the Imperial Court. The metropolitan of any province with such a petition could have it facilitated by sending it in writing to the bishop where the Emperor was currently holding court. That court was in session in Ravenna, not in Rome. There was therefore nothing in the canons that required the petition to be carried to Rome, and certainly nothing that gave Rome the final say in the matter. The bishops of Africa were therefore right to complain that Faustinus had arrived under the false pretenses “of asserting the privileges of the Roman Church,” privileges that neither Sardica nor Nicæa had granted to it.

What is more, Zosimus had also violated Canon 5 by sending Faustinus not as a neutral arbiter but as counsel for the defense, with threats rather than with objectivity. Of this last violation, the African synod complained emphatically:

“Faustinus … acted rather as an advocate of the aforementioned person [Apiarius] than as a judge, … what was more the zeal of a defender, than the justice of an inquirer.” (Canon 138, Epistle of the African synod to Pope Celestine)

That was a complete and utter rejection of Constantine’s reforms which were intended to guarantee an independent judiciary. Now it was Zosimus who was playing the part of the Eusebians “who relied more upon violence than upon a judicial enquiry” (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part I, chapter 3, Letter of the Council of Sardica, paragraph 37).

In sum, Apiarius had violated Canon 14 of Sardica by not taking the matter up with the metropolitan in Alexandria, Zosimus had violated the appellate process first by taking up Apiarius’ appeal and second by granting communion to him before the case was legitimately resolved through the appellate system. Zosimus had violated Canon 9 first by ruling on the case without investigating it “in order that he may first examine them, lest some of them should be improper,” and second by imposing the sententiam without having it reviewed and ratified by a higher court, and had violated Canon 5 by sending Faustinus not as a neutral arbiter but as counsel for the defense, with threats rather than with objectivity.

So far from acting in accordance with the Canons of Sardica, Zosimus was in fact acting against both the spirit and the letter of that council. All of this was fraudulently advanced on the authority of Nicæa, and in plain violation of the actual canons of Sardica that Zosimus had cited.

The bishops in Carthage were therefore justifiably shocked at the impropriety of the demands. Surely Faustinus must have brought with him, in addition to the acquittal, actual evidence so that Apiarius might “be cleared of the very great crimes charged against him by the inhabitants of Tabraca” (Canon 138, Epistle of the African synod to Pope Celestine). How could the sentence of Urban be reversed without it? Surely Faustinus had arrived as a neutral arbiter to conduct an inquiry and investigate the matter! Surely Faustinus had come to help Zosimus compile his sententiam to be forwarded to Emperor Honorius in Ravenna where the matter could be finally resolved! Surely this was the beginning of an appeal, not the end of one!

Nothing doing. The purpose of Faustinus’ visit was to enforce a sentence, not to participate in an appeals process in accordance with the canons of the church.

To their credit, the African bishops objected on the further grounds that Zosimus was wrongly attempting to invoke Nicæan authority to establish Roman Primacy. Alypius of Numidia objected, saying that Zosimus had invoked the wrong council:

“[W]e shall ever observe what was decreed by the Nicene Council; yet I remember that when we examined the Greek copies of this Nicene Synod, we did not find these the words quoted.” (Introduction)

Faustinus, of course, was offended that the decree of an imperial Roman bishop was even in question, and protested that Rome was insulted by the very suggestion:

“Let not your holiness do dishonour to the Roman Church, either in this matter or in any other, by saying the canons are doubtful, as our brother and fellow bishop Alypius has vouchsafed to say.” (Introduction)

Nevertheless, the Council of Carthage sought copies of the Nicæan statutes from the bishops of Antioch, Alexandria and Constantinople in order to compare notes. This controversy spanned the pontificates of three popes—Zosimus (417 – 418 A.D.), Boniface I (418 – 422 A.D.), and Celestine I (422 – 432 A.D.)—and when authentic copies of the council of Nicæa were examined, the African church wrote to Celestine, correctly informing him that Zosimus had been invoking the wrong council the whole time:

“Because with regard to what you have sent us by the same our brother bishop Faustinus, as being contained in the Nicene Council, we can find nothing of the kind in the more authentic copies of that council.” (Canon 138, Epistle of the African synod to Pope Celestine)

We note that by this time the African synod is responding to a recent communication from Celestine’s court, carried to Africa in the hands of one Leo of Rome. In that communication, Pope Celestine was still rejoicing over the unlawful acquittal of Apiarius, and in response the Africans were still objecting to Zosimus’ violation of Sardician protocols and the gross misrepresentation of the canons (Canon 138, Epistle of the African synod to Pope Celestine). Thus, after three consecutive pontificates during which the African church continued objecting to Zosimus’ incorrect appeal to Nicæa and intentional violation of Sardica, the pope was still rejoicing in the gross violations of the appeals process, and Africa was still protesting it. It had been no small affair, and nobody in the inner circle of Roman affairs could possibly have missed it.

Our attention must therefore now turn to Leo, the man who would soon be known as Pope Leo the Great. Leo, apparently, was a trusted member of Celestine’s court, and highly respected throughout the empire. It was he who had carried the letters to Africa from Celestine, and as Augustine notes, it was he who had carried messages to Aurelius from then-presbyter Sixtus as well (Augustine, Letter 191, paragraph 1). A full ten years before the pontificate of Leo, John Cassian dedicated his extensive work, On the Incarnation, to him, “my esteemed and highly regarded friend, ornament that you are of the Roman Church” (John Cassian, On the Incarnation, Book I, preface). When Emperor Valentinian III needed to resolve a dispute between Aetius and Albinus in Gaul, he sent Leo on the secular diplomatic mission.

As a respected member of the Roman clergy decades before his pontificate, Leo had carried messages back and forth between the disputing parties in the matter of the acquittal of Apiarius and therefore had first-hand knowledge of the dispute. Through considerable investigation, Africa managed to prove that Zosimus had misquoted and misapplied the canons in question, and Leo himself had seen the whole controversy unfold before him. So disturbing and contentious was the conflagration that a prominent Roman clergyman could only miss it by sleeping through the first half of the 5th century. It would be impossible to be ignorant of the glaring misrepresentation of Zosimus in his overtures to the African court, and that court’s subsequent correction of his error.

For this reason, Leo is doubly inexcusable: both in his continued use of the Sardician Canons to claim exclusive Roman authority to hear appeals, and in his continued claim that the appellate authority had originated in the canons of Nicæa. What the African court had disparaged as Zosimus’ “pretence of asserting the privileges of the Roman Church,” became under Leo the rallying cry of his pontificate. A cursory examination of his correspondence makes this quite clear. Under Leo, conflating the canons of Sardica and Nicæa was not a mistake to be corrected; it was a tool for administering the Church.

Letter 6, to Anastasius, Bishop of Thessalonica (444 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo invokes the appeals process of Sardica that “we reserve to ourselves points which cannot be decided on the spot and persons who have made appeal to us.” He instructs Anastasius to “send your report and consult us, so that we may write back under the revelation of the Lord.” This, says Leo, is in according to “our right of cognizance in accordance with old-established tradition and the respect that is due to the Apostolic See” (paragraph 5).

Letter 14, to Anastasius, Bishop of Thessalonica

In this letter, Leo conflates Sardica Canon 5 and Nicæa Canon 5, making them one. The 5th of Nicæa established that synods be held “in each province twice a year” to resolve disputes (Nicæa, Canon 5), and the 5th of Sardica required that appeals to Rome, if desired by the appellant, could be handled by the bishop there (Sardica, Canon 5; see also Canon 9). Leo simply combines the two and says that according to Nicæa, appeals from the two biannual synods must be transferred to Rome for resolution:

“Concerning councils of bishops we give no other instructions than those laid down for the Church’s health by the holy Fathers: to wit that two meetings should be held a year, in which judgment should be passed upon all the complaints which are wont to arise between the various ranks of the Church. …. and if, after both parties have come before you, the thing be not set at rest even by your judgment, whatever it be, let it be transferred to our jurisdiction.” (paragraph 8)

Letter 16, to the Bishops of Sicily (447 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo again conflates the 5th of Nicæa and the 5th of Sardica, insisting that the Sicilian bishops “send three of their number to each of the half-yearly meetings of bishops at Rome” in accordance with “the wholesome rule of the holy Fathers that there should be two meetings of bishops every year.” Leo continued,

“[A]nd this council must always meet and deliberate in the presence of the blessed Apostle Peter, that all his constitutions and canonical decrees may remain inviolate with all the Lord’s priests” (paragraph 8).

Letter 24, to Emperor Theodosius II (449 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo complains that bishop Flavian of Constantinople had deprived presbyter Eutychus of communion (paragraph 1), and insists that full documentation must be sent to Rome in order for him to make a judgment in the case:

“[W]e must be informed of the points on which he [Flavian] considers him [Eutychus] unsound, that the right judgment may be passed after full information … because the method of our Faith and the laudable anxiety shown by your piety requires the merits of the case to be known.” (paragraph 2)

Here, Leo is claiming that the “method of our Faith”, i.e., the canonical appeals process, requires that the matter of a deposed presbyter be heard in Rome. Remarkably, this is precisely the scenario that caused the eruption in Africa when presbyter Apiarius appealed to Rome after being deposed by bishop Urban of Sicca in violation of the 14th of Sardica. According to Canon 14 of Sardica, the deposed presbyter was to await the outcome of his appeal, and if the accused chose to appeal the sententiam of the metropolitan (Flavian in this case), the petition was to be forwarded to whichever city where the Emperor was currently holding court. That city was Constantinople, not Rome. In receiving the appeal of Eutychus, Leo was not only violating Canon 14 of Sardica but was usurping the prerogatives of the Emperor as defined in Constantine’s judicial reforms that had been canonically received by the church under bishop Hosius in 343 A.D..

Letter 33, to the Synod of Ephesus (449 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo writes to the synod, affirming the request of the Emperor to remand the decision to Rome for a final decision. “[O]ur most clement prince” was right, Leo wrote, to pay “such deference to the Divine institutions as to apply to the authority of the Apostolic See for a proper settlement.” (paragraph 1). As we shall see in letter 44, Leo was again conflating Sardica and Nicæa in Letter 33.

Letter 44, to Emperor Theodosius (449 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo requests “a general synod to be held in Italy, which shall either dismiss or appease all disputes in such a way that there be nothing any longer either doubtful in the Faith” (paragraph 3). He insists that “the bishops of the Eastern provinces must come” (paragraph 3) because the canons of Nicæa required that such appeals be heard in Rome:

“And how necessary this request is after the lodging of an appeal is witnessed by the canonical decrees passed at Nicæa by the bishops of the whole world, which are added below. ” (paragraph 3)

Letter 56, From Galla Placidia Augusta to Theodosius

In this letter the Augusta affirms the decision of Flavianus who “had sent an appeal to the Apostolic See, … in accordance with the provisions of the Nicene Synod.” This letter is from the “perpetual Augusta and mother” Galla Placidia, but in it she is relating to the Emperor what she had heard about the Catholic Faith from Leo: “the most reverend Bishop Leo waiting behind awhile after the service uttered laments over the Catholic Faith to us.” Apparently those “laments” included the alleged “Nicene” requirement that appeals be heard in Rome, which again was a conflation and misappropriation of Nicæa and Sardica.

Letter 85, To Anatolius, Bishop of Constantinople (451 A.D.)

Leo insists in this letter that “concerning those who have sinned more gravely … let their case be reserved for the maturer deliberations of the Apostolic See” (paragraph 2).

Letter 105, to Pulcheria Augusta (452 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo appeals to the “canons which many long years ago in the city of Nicæa were founded upon the decrees of the Spirit” in order to condemn the practice of indulging carnal ambition by translating from smaller to greater dioceses, or “to pass from the lowest to the highest things” (paragraph 2). Here Leo conflates the 1st of Sardica which prohibits bishops from translating “from an humble to a more important see” (Sardica, Canon 1) with the 15th of Nicæa that prohibits presbyters and deacons from “transfer[ring] from city to city” (Nicæa, Canon 15). Nicæa prohibited translations, but Sardica prohibited translations from smaller dioceses to larger ones for the purposes of aggregating power, esteem and influence.

Letter 117, to Julian, Bishop of Cos (453 A.D.)

In this letter, Leo writes “to show that I approved of what was resolved upon by our holy brethren about the Rule of Faith” at Chalcedon, and does so “on the absolute authority of the Nicene canons” (paragraph 1), as if Nicæa had insisted that all disputes and councils were to be ratified by Rome. Again, Leo had conflated Nicæan and Sardician canons, the former of which required that all disputes be resolved, and the latter of which allowed that Rome was one venue among many through which appeals could be handled.

What becomes clear on review of the history of the debacle—from the invalid appeal of presbyter Apiarius of Sicca, through Leo’s affirmation of Chalcedon—is that in Rome, the canons of Sardica were hopelessly conflated with the canons of Nicæa. Even after a stern and well-documented rebuttal to Zosimus’ overtures, Rome had stunningly opted to allow the conflation, and took advantage of the resulting confusion by treating as one, two councils that had been convened eighteen years apart.

What is also evident is that Leo cannot possibly have been ignorant of the impropriety of the conflation, or the fraud that was being perpetrated upon the world by the deceptive historical revision. Leo was a high-ranking clergyman in Rome throughout the entire affair, and was a man of great political and ecclesial accomplishment. One does not arrive at that point completely ignorant of the complaint the Africans had made against his predecessor Zosimus, or of the sound canonical grounds upon which they based their objections.

We therefore agree with the summary of Charles Gore in his analysis of Leo:

“He urged a false plea when he urged the Canon of Nicaea as justifying his claims of universal appellate jurisdiction, and he can hardly have urged it ignorantly” (Gore, Charles, D.D., Leo the Great (London: Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd, 1912), 137).

Pope Leo was guilty of intentional conflation of the canons of Sardica and Nicæa, and knew full well what he was doing. Gore concludes, justifiably:

“However much, then, the canons of Sardica may at Rome have been regarded as an appendix to those of Nicæa, no pope after this [the dispute over Apiarius] could, without deliberate misquotation, quote the appeal-canon as having Nicene authority. He could not plead ignorance after this clear demonstration. It must therefore be admitted that Leo in urging, as he constantly did, Nicene authority for receiving appeals from the universal Church, was distinctly and consciously guilty of a suppressio veri at any rate, which is not distinguishable from fraud.” (Gore, 114-15)

Fraud is precisely what Leo had perpetrated by repetition as he shamelessly led the charge to persuade the world of something the Nicene Canons cannot possibly be shown to support: Roman primacy.

The effect of his repetition may be seen in how his legates behaved at Chalcedon in 451 A.D.. The Latin contingent objected to Canon 28 that had claimed for Constantinople the primacy over several Eastern dioceses based on the 3rd Canon of Constantinople. After all, the Imperial Court and the Senate had relocated there—it only made sense for Constantinople to enjoy the same privileges of Old Rome:

“[T]he city which is honoured by the imperial power and senate and enjoying privileges equalling older imperial Rome, should also be elevated to her level in ecclesiastical affairs and take second place after her.” (Council of Chalcedon, Canon 28).

The Latin contingent responded, ironically, by accusing the Eastern bishops of violating the Canons of Nicæa, claiming that they had set aside the wisdom of the 318 bishops in 325 A.D. and substituting for them the canons of the 150 bishops in Constantinople of 381 A.D.. Just as with the dispute over Apiarius, there was only one thing that could possibly resolve the dispute: “Let each side present the canons [of Nicæa]” said the president of the council (Richard Price & Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, vol 3, in Gillian Clark, Mark Humphries & Mary Whitby, Translated Texts for Historians, vol 45 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005) 85).

This time, the legates of Rome were prepared. The Easterns brought forward the canons, and cited the 6th of Nicæa as follows:

“Let the ancient customs in Egypt prevail, namely that the bishop of Alexandria has authority over everything, since this is customary for the bishop of Rome also.” (Price & Gaddis, vol 3, 86)

The Roman presbyters produced the same canon, but with one, modest editorial modification:

“The church of Rome has always had primacy. Egypt is therefore also to enjoy the right that the bishop of Alexandria has authority over everything, since this is the custom for the Roman bishop also.” (Price & Gaddis, vol 3, 85)

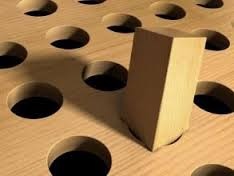

Clearly, the 318 bishops at Nicæa had asserted no such thing about the antiquity of Roman Primacy. No such language could be found in all the ancient records of Nicæa. But the facts of history were no obstacle for Leo. He had dealt long enough with the galactic incongruity between his ambitions for Roman primacy and the lack of historical and canonical evidence to support them. By the relentless power of repetition, and with some creative editorial modifications to the canons of Nicæa, the square peg of Roman primacy was finally pounded into the round hole of a history that could not possibly accommodate it except by the hammer of deceit and fraud.

To add to the criminality as well as to the farce of Leo’s primal ambitions, all of this was done while Leo continued insisting that the Canons of Nicæa were for all time inviolate, and could “never be modified by any change,” or “perverted to private interests”:

“These holy and venerable fathers who in the city of Nicæa, after condemning the blasphemous Arius with his impiety, laid down a code of canons for the Church to last till the end of the world, survive not only with us but with the whole of mankind in their constitutions; and, if anywhere men venture upon what is contrary to their decrees, it is ipso facto null and void; so that what is universally laid down for our perpetual advantage can never be modified by any change, nor can the things which were destined for the common good be perverted to private interests.” (Leo the Great, Letter 106, paragraph 4).

Mmmm, hmmm. That’s right. We must never modify those unalterable Nicæan canons. <wink, wink>.

Gore summarizes for us the immeasurable consequences of Leo’s criminal revisionism:

“Of this crime we cannot acquit him ; and how large a part this and similar ‘lies’ which they are none the less, though they be believed to be ‘for God’ have contributed to the advancement of the Roman see, it is quite impossible to estimate.” (Gore, 114-15)

Leo ended up succeeding in his efforts, and even Anatolius, Bishop of Constantinople ended up writing a letter to Leo, submitting to him and apologizing for the behavior of the Eastern bishops at Chalcedon (Leo the Great, Letter 132, from Anatolius, Bishop of Constantinople, to Leo).

Conclusion

Our objectives in this series were to summarize the Roman Catholic reliance on Sardica to prove Roman Primacy, as well as to show how the Canons and correspondence of Sardica can only make sense through the lens of the reformation of Constantine’s judiciary. Otherwise it makes no sense for “pope” Julius to complain that the Eusebians had not written to him first, immediately after complaining that they had written to him first and that they should not have done so (Athanasius, Apologia Contra Arianos, Part I, chapter 2, Letter of Julius to the Eusebians at Antioch). When viewed through the lens of Constantine’s reforms, it is quite clear that Julius believed the Eusebians had violated canon by writing to him alone instead of to all bishops, and had violated custom by not responding to his subpoena when he requested additional information about the case in Alexandria. That custom is what Hosius canonized at Sardica. Far from canonizing Roman Primacy, Sardica stood in judgment of Rome’s decision, allowed other ways of getting an appeal to the Imperial Court apart from Rome, and required that all further such appellate decisions from Rome must be submitted to the Imperial Court for approval prior to execution.

Ignoring this context, popes like Zosimus, Boniface, Celestine and Leo the Great took advantage of the Sardician canons, conflated them with those of Nicæa, and then used them as a bludgeon to compel the world into submission to Rome on the fraudulent pretense of asserting the Nicæan primacy of the Roman Church. This from the men who claimed to be representatives on earth of Him “who went about doing good … for God was with Him” (Acts 10:38).

We conclude this series by reminding our Christian readers that Leo’s religion is the one that former protestants like Bryan Cross, Jason Stellman, Taylor Marshall and many others desire for us to join with them. They may keep their Roman Primacy, founded as it is upon a lie, and rest comfortably in this life in the fraud that sustains their belief that they have found the true Church. Those fraudulent statutes will not help them in the next.

We, for our part, stand with the Lord Who commanded us, and Leo, as well as Bryan, Jason and Taylor:

“Thou shalt not raise a false report: put not thine hand with the wicked to be an unrighteous witness. Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil; neither shalt thou speak in a cause to decline after many to wrest judgment.” (Exodus 23:1-2)

“Come out of her, My people….” (Revelation 18:4)

Follow

Follow

TIM-

You said: “Those who have been keeping up with this series will recognize that the canon Zosimus cited was not from the Council of Nicæa in 325 A.D., but from the Council of Sardica in 343 A.D.. That was just one of Zosimus’ errors.”

But here is the rest of the story: Zosimus became involved in a dispute with the African bishops in regard to the right of appeal to the Roman see by clerics who had been condemned by their local bishops. When the priest Apiarius of Sicca was excommunicated by his bishop on account of his alleged crimes, he appealed directly to the pope, without regard to the regular course of appeal in Africa. The pope accepted the appeal and sent out his legates to Africa to investigate the matter.

Zosimus based his action on a reputed canon (decision) of the First Council of Nicaea, an ecumenical council binding on the whole church. Embarrassingly, it was in reality a canon of the more localized Council of Sardica. This mistake resulted from the fact that in the Roman manuscripts, the canons of Sardica followed those of Nicaea immediately, without an independent title. The African manuscripts contained only the canons of Nicaea, so that the canon appealed to by Zosimus was, of course, not contained in the African copies of the Nicene canons. Thus, a serious disagreement arose over the appeal, which continued after the death of Zosimus.

And that is just one of your omissions. More to come…

Bob,

From the same article you cited, “He later misstepped in using a supposed decision of the Council of Nicaea to bolster Rome’s prerogatives, when in fact no such rule was passed at Nicaea.” A more accurate way to say it, therefore, is that the canon appealed to by Zosimus was, not contained in the African copies of the Nicene canons, or in any legitimate record of the Nicæan canons in the world. Thus, the infallible vicar of Christ who cannot err in matters of faith and morals when he speaks from the chair didn’t even know what council he was citing, and the canons he cited were cited out of their context.

Could you help me understand what you think I omitted? The article you cited is consistent with my representation of the affair. Were the Sardician canons an appendix to the Nicæan canons in Rome? Of course they were. That’s what Gore said when I cited him in the article from which you think I omitted that critical data:

Thus, throughout the article, I said that Zosimus had conflated the canons of Nicæa and Sardica, and conflate means, to combine two texts or ideas, etc.. into one. You said, “the canons of Sardica followed those of Nicaea immediately, without an independent title,” as if I had omitted the fact that Sardica and Nicæa had been conflated. But that’s what conflation means.

What did I omit? That Rome was right to do so?

Thanks,

Tim

TIM–

You asked: “What did I omit? That Rome was right to do so?”

My apologies. You quoted it later concerning Pope Leo. You just made it sound like Zosimus had conflated the canons of Nicæa and Sardica, on purpose, and that he was responsible for deliberately causing the problems by deception instead of mistakenly relying on an unknown clerical error at the time.

Notice I was quoting what you were saying about Zosimus and not Leo.

Thanks, Bob. I understand. I think we can agree that Rome’s copy of the canons was erroneous. My intent was to show that Zosimus had been using the wrong canons, extracted them from their original context, and in the process violated the very Sardician canons he was citing as Nicæan. Thus, the article you cited had Apiarius (and therefore, Zosimus with him) violating “the regular course of appeal.”

In any case, I think we can also agree that Zosimus (and Rome with him) was ignorant of the history of the two councils Rome had conflated, and in his ignorance of Church Councils and church history, he made a mistake on a matter of faith and morals in the exercise of an act that he very much believed to be the prerogative of the chair of St. Peter. We can categorize this whole sordid episode as an early exercise in papal “infallibility.”

Thanks,

Tim

Again, I think the doctrine of papal infallibility is fallible in itself. The actions of historical popes prove it. Popes are human and can make mistakes. However, I do not think they deliberately teach bad faith or bad morals. There is no doubt in the primacy of Peter as recognized by the ECF’s in the Apostolic See, or their would be no distinction of the Chair of Peter. That is established fact. You acknowledge that the geographic location of that Chair is in Rome. You also claim that the authority of the Chair of Peter is not exclusive to the geographic location but is shared amongst the separate bishops.

So, why did they address the bishop of Rome “Your Holiness”? Why aren’t the other bishops addressed that way? Geographic location?

Bob,

Pssssst, Watch these videos. Tim told me once he didn’t think catacomb art means anything so don’t let him see it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kAHwie7lmM

He thinks there was no papacy either so keep this one out of his reach or he could hurt himself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmEAuLNoP-Q

But do make him watch this one. It’s about “Bible-Believing churches”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsIoiWO96JI

Tim says the Catholic Church’s Sacramental system is a later development. Ha!

This one is my favorite.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoVJM_dkbjk

Would you believe Ken Temple turned me on to this stuff!?!?

JIM–

You said: “Tim told me once he didn’t think catacomb art means anything so don’t let him see it.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kAHwie7lmM

I am going through these videos. This first one is really good to get pieces of “the rest of the story”. I was fascinated by the common sense thinking here. In particular about the Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians. What prompted Clement to write it in the first place? The Corinthians wrote a letter to Rome! Really? An underground persecuted church that is closer to Jerusalem, that is closer to Alexandria, that is closer to

Antioch, instead wrote to, of all people, Clement, the bishop of Rome. Why? Could the answer be primacy?

I wonder………

Bob wrote:

“An underground persecuted church that is closer to Jerusalem, that is closer to Alexandria, that is closer to Antioch, instead wrote to, of all people, Clement, the bishop of Rome. Why? Could the answer be primacy?”

Yes, Presbyterianism has begun. Biblical Presbyterianism as Tim has shown very clearly was growing in the early church, and has nothing to do with a one man Papal system.

You guys are really confused if you think writing letters to a Bishop confirms the Popish form of church government. As the last series showed, it was clearly showing the roots of a Biblical Presbyterian form of government.

JIM–

You said: “He thinks there was no papacy either so keep this one out of his reach or he could hurt himself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmEAuLNoP-Q

After watching this video, it seems to me that Tim is leaving out a lot of things in his analysis of the primacy of Rome that would damage his theory. I would like to see these guys debate Tim’s theories point by point.

JIM–

You said: “But do make him watch this one. It’s about “Bible-Believing churches”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsIoiWO96JI

This sure sheds a different light on the “Great Apostasy”, doesn’t it? Common sense trumps conspiracy theory every time.

Bob wrote:

“This sure sheds a different light on the “Great Apostasy”, doesn’t it? Common sense trumps conspiracy theory every time.”

Man is it painful to listen to the chatter from Jim and Bob seeking to toss out conspiracy theory arguments, when they have no earthly idea that this video explains the presupposition of the author. He was an extremely liberal Southern Baptist (the most liberal and Romish of all Baptists), and he proves it with his own testimony. It has nothing to do with conspiracy theory, it has to do with this man was always Romish AT HEART and just needed the push by worshiping and following idols to take the full time leap to Rome. He declares he was an Evangelical and the Evangelicals have already sworn an oath to Rome.

For those who want to learn about the results of this agreement, see here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gh_mWAnkJ8U

“In March 1994, a group of 20 leading Evangelicals and 20 leading Roman Catholics produced a document called Evangelicals and Catholics Together. The two main instigators were Richard John Neuhaus who was a Roman Catholic priest, and Charles Colson who was the founder of Prison Fellowship. Soon after this publication Pastor Steve Van Horn interviewed Richard Bennett on the consequences of movement that it had started. Richard clearly showed that while the authors claimed that Evangelicals and Catholics are one in Christ, in fact, this claim is an utter fallacy. Now in the 21 century, the same fallacious hullabaloo continues. Rather than compromise the Gospel, we are to separate from those who promote such heresy and “earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered to the saints.” We request that you make this DVD known to others. If possible, please link to it, or have it placed on an Internet Website or Blog. Thank you.

http;//www.bereanbeacon.org”

WALT–

You said: “Man is it painful to listen to the chatter from Jim and Bob seeking to toss out conspiracy theory arguments, when they have no earthly idea that this video explains the presupposition of the author.”

Everybody has their presuppositions, even Richard

Bennett. His troubles are not unlike any other persons who were immature in spirit and making life choice. And I’ll be the first to tell you the Catholic Church is terrible about teaching why they do what they do. Their adult Sunday school is practically non-existent compared to the First Baptist Church or the United Methodist Church or Denton Bible Church.

And I notice that you, Walt, did not receive an education on the Church of Scotland from going to Sunday school. You had to search it out for yourself. And the reason you went searching is because you felt you weren’t being “fed” in the church(s) you were attending.

And you also said: “You guys are really confused if you think writing letters to a Bishop confirms the Popish form of church government. As the last series showed, it was clearly showing the roots of a Biblical Presbyterian form of government.”

In the writings of the ECF’s, there is a distinction in presbyters and bishops and they are treated differently. It is clearly Episcopalian and not Presbyterian.

TIM–

You said: “We must keep in mind that the context of the canons of Sardica was that of correctly appealing to the Imperial Court. The metropolitan of any province with such a petition could have it facilitated by sending it in writing to the bishop where the Emperor was currently holding court. That court was in session in Ravenna, not in Rome. There was therefore nothing in the canons that required the petition to be carried to Rome, and certainly nothing that gave Rome the final say in the matter. The bishops of Africa were therefore right to complain that Faustinus had arrived under the false pretenses “of asserting the privileges of the Roman Church,” privileges that neither Sardica nor Nicæa had granted to it.”

If this is truly the case, then why appeal to Rome in the first place? [Bishop Urban of Siccas in Egypt had deposed presbyter Apiarius of Tabraca for moral turpitude, and Apiarius immediately appealed to pope Zosimus of Rome.] What is so special about Rome that causes those people to appeal to it? Didn’t the word get out that there is nothing special about Rome? That Rome has no sway over any other episcopate? That you are wrong to appeal to Rome? I guess Apiarius didn’t get the memo either.

There is an elephant in the room that no one is paying any attention to. If, as you say Tim, that the Emperor was the final say-so in Church matters, then that makes the Emperor the Vicar of Christ and not the Bishop of Rome! So that makes Caesar the anti-Christ instead of the Pope.

The Puritan Hard Drive (PHD) is the single largest one-time digital publishing event of Puritan, Reformation, Reformed Baptist, Reformed and Biblical Presbyterian and Covenanter resources ever produced. Combine all of this with the very useful PHD software and there are many reasons to rejoice for such an unprecedented Puritan and Reformed Bible study tool.

As a Reformed Baptist pastor, it is also interesting to note, that the Puritan Hard Drive contains 2,208 Reformed Baptist books, MP3s and videos. Spurgeon, Bunyan, Pink, Fuller, Gill, Griswold, Pollard, Bennett, along with many others can be found here. The PHD also contains a very large number of for Reformed Presbyterian resources (books, MP3s, videos) and Reformed commentaries, including a number of very rare and valuable commentaries and commentary sets that most people are not likely to have access to outside the PHD. All of these resources are easy to access by just clicking on the “Select Category from List” button on the main search screen.

Additionally, the affordable price for both the downloadable and USB Puritan Hard Drive versions (Windows and Mac), makes this a must have Reformed resource for all of God’s people. Moreover, Still Water Revival Books’ (SWRB, who are the creators of this program) also allows every family member in the same house to legally use the Puritan Hard Drive on all their devices. Thus, whole families can be blessed together, growing in holiness by drinking deeply from the wells of truth set forth by the best Christian teachers throughout history.

Imagine having access to over 12,500 Puritan and Reformed resources right at your fingertips. Imagine being able to instantly search out what the Puritans have said concerning various Bible topics with the click of a button. Imagine the time you would save studying the Bible, preparing sermons and Bible studies, doing writing projects. Imagine the depth of knowledge and insight one would gain from those great giants in the faith who have gone before us. The Puritan Hard Drive offers all this, and much more.

For example, though there are many ways to slice and dice the information, the Puritan Hard Drive contains (using the easy-to-use and powerful proprietary software) a Master Full Text Search feature which is particularly useful. Using this search you can quickly locate every word, phrase, or Bible verse (or verses), across all the searchable text on the PHD. This kind of research power has never before been available to Christians, especially as it pertains to such a large group of the best Puritan and Reformed resources from throughout history right up to our day, including many rare Puritan and Reformed classics that are unavailable elsewhere or that would cost large sums of money to obtain. With the click of a button, a massive number of search results come to you alphabetically by title (with the author included) so you can quickly scan down the list of titles and authors to find what you want. When you want to explore deeper into a book you simply click the icon to the left of the title and you will see all your search terms, with each search term in the context of one line in that book.This helps you to quickly determine if the results in a given book provide the exact information you are seeking. This feature also allows you to cover a vast amount of material in a short amount time. When you find precisely what you are looking for, just click on that particular line and you are instantly taken to the right book, already opened to the right page, and your search result is highlighted so you can see it on the page immediately.

Depending on what you are searching for, results can come in the hundreds to hundreds of thousands. In fact, you can accomplish thousands of hours of research in moments with the Puritan Hard Drive. This not only gets you to the precise truth you are seeking, but it also does it faster than ever before possible. What’s more, most of this kind of research would be humanly impossible outside the Puritan Hard Drive, as the PHD can dig deeper and faster than thousands of people, and can complete these searches in a small amount of time. For instance, as noted on Still Waters Revival Books’ Web page, a search for the word “prayer” brings up 97,170 search results in 1,378 documents. Being able to search so quickly and accurately, through many of the best Christian resources from throughout history, allows for the most extensive and deepest research ever available on any topic you want.

Also, the Manual for the Master Full Text Search feature on the PHD, which is entitled “How to Find Specific Words and Phrases in Searchable Books.pdf”, contains a number of screen shots that are easy-to-follow and it will help you use this wonderful feature to its full potential. When you see what the Master Full Text Search feature does, I think you will be very pleased that such great research capabilities have been placed in your hands.

Of course, the Master Full Text Search is just scratching the surface concerning what the Puritan Hard Drive can do. You can even add your own notes to every resource and the Puritan Hard Drive will save them for you, then you can use a special search to find specific notes you made or you can search for your own notes mixing and matching many other search criteria. Also, many search features can be mixed and matched to produce whatever level of detail you want. From the beginner, to the power user, the PHD provides you with broad or exact results and everything in between, as you have total control over the complete research process with pinpoint accuracy.

Furthermore, included is a very helpful PDF manual that can walk you through each feature. This manual is filled with clearly written instructions and screenshots showing you exactly where to move your mouse to make the best use of all the features on the PHD. Even better than that, SWRB provides tutorial videos at PuritanDownloads.com that show and tell you exactly how to get the most out of your Puritan Hard Drive. For these tutorial videos just click on the link “ALL PURITAN HARD DRIVE VIDEOS” (without the quotation marks) in the left column at PuritanDownloads.com. The first two videos on this page are overviews of the Puritan Hard Drive and all the videos that follow are tutorial videos. All these videos are YouTube videos so it is easy to pause and rewind each video as you learn. You can even run the videos with the Puritan Hard Drive opened, listen to a point where the video shows you how to do something, pause the video, do the action stated on the PHD, and repeat, until, you master all the features at your command. The PHD was designed to allow you to mix and match the capabilities of many of the study tools it contains, to obtain the best research results possible, and following these videos is the best (and fastest) way to make optimal use of the PHD.

Concerning the creating of the PHD, Dr. Reg Barrow (the president of SWRB) mentioned to me that he saw the Lord answer many prayers, over the 26 years it took to produce the product. Knowing that the Lord so closely watched over all aspects of the development of this product has given the brothers at SWRB an earnest desire to share the treasures of our Lord’s truth found on the PHD. This is why SWRB has implemented a monthly payment plan for those who cannot afford the PHD in one payment. Just contact them, using the contact information at PuritanDownloads.com and let them know your situation and they will do their best to help you obtain this resource at a price you can afford.

A host of others have also endorsed the Puritan Hard Drive. Among them are Paul Washer, Dr. Joel Beeke, Dr. Voddie Baucham, Richard Bennett, Paul Barnes, Greg Price, Dr. Matthew McMahon, Jim Dodson, Dr. Steven Dilday, Brian Schwertley, and John Hendryx (Monergism.com). If you would like to see more reviews about the Puritan Hard Drive, including reviews by everyone mentioned above, just click on the link “Puritan Hard Drive Reviews” (without the quotation marks) near the top of the left column at PuritanDownloads.com.

In sum, the Puritan Hard Drive is an amazing resource; I wish I had known about it sooner. I strongly commend it to you for your own spiritual growth and as a blessing for your entire family. To me, it is one of the best Christian study tools available on the market today.

– Rob Ventura, Pastor, Grace Community Baptist Church, North Providence, Rhode Island, Co-Author of A Portrait of Paul and Spiritual Warfare and a contributor to the Reformation Heritage KJV Study Bible, Etc.

For those who would like to see “the other side of the story” on Roman Catholic’s see this video here. This is some of the best investigative research one will find on YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e8bzxstPBUM

Published on Nov 1, 2013

Satan’s Papacy was born in 312 AD with Constantine becoming the first Papal Caesar The pagan Council of Nicea (325) solidified and defined his power. Since 1814 the Jesuit General (the Black Pope) has controlled the Papacy. If a Pope becomes disobedient or rebellious to the Black Pope’s commands, he is punished (like Pope Pius IX) or is murdered (like Pope John Paul I). Thus, the Jesuit General was in command of Vatican I (1870) and Vatican II (1963-65). All the lasting decrees of those Councils were written from Jesuit penholders (like Cardinal Avery Dulles presently at Fordham University in New York). In conclusion, neither the Council of Nicea nor the Second Vatican Council hijacked the Vatican. The Jesuit General, using his military Company of Jesus, hijacked the Papacy in 1814 and has retained his absolute power over the Vatican Empire since that fateful year Whatever the Jesuits wish for the United States, THE JESUITS GET through its Council on Foreign Relations controlled by the Jesuits brothers the Sovereign Military of Malta headed in the region within New York (The EMPIRE STATE) by the Maltese Knights of the Round Table headed by the Archbishop of New York governed by georgetown university Georgetown University rules the United States and its second in command Fordham University. SMOM Knight Ronald Reagon was pictured with JESUIT masters at GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY as was clinton biden rome rules,the Order backed Hitler and controlled his SS. After the war the SS became the Cold War’s CIA—the heart of the Black Pope’s International Intelligence Community–and govern the Mossad. mi6 go to the unhivedmind.com . vaticanassassins,org for more revelation.

WALT,WALT,WALT!

I knew it!! The Pope can’t be the anti-Christ, it’s the Jesuit General all along–The Black Pope. He is the one who caused the Reformation. He is the one who keeps the Church in turmoil and in dis-unity. That is his whole purpose is to divide the Church so that it cannot stand. Popes have lived and died, but the Jesuit General has lived and never died from the Church’s beginnings. He was the one who usurped Rome’s authority in 325 AD with the judicial appellate system that the heretical Arians and Montanists and Donatists took advantage of. He was the one who led those people away from orthodoxy and into heresy. Now that’s the real character of Anti-Christ!

Thx so much Tim. It is very interesting to learn about this history and how it fits with the material you have written on the Fifth Empire.

Very interesting to note also the placement of Chalcedon, at 451ad, and it’s mixed influence after the rise of Rome.