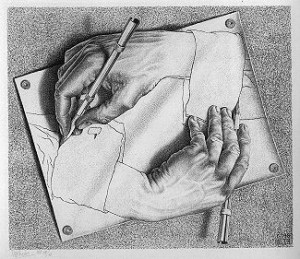

M. C. Escher’s Drawing Hands shows two drawn hands drawing each other, each hand getting its power to draw from the other. True to Escher’s style, a paradox is presented to the eye of the beholder, and the paradox is never resolved—the eye must continually move from one object to the other. Each time the eye settles on an apparently solid 3-dimensional object that can make sense of the rest of the picture, the paradox reappears. The search for the original, “authoritative” hand never ends.

We believe this is a good illustration of Roman Catholicism’s view of Tradition because Tradition is based on what Rome teaches, and what Rome teaches is based on Tradition. We gave an example of this in our recent post, All the Way Back. In that post, Roman priest and Marian devotee, Fr. Thomas Livius, showed the origins of Marian doctrines from the Fathers of the first six centuries. When he arrived at the teachings of Origen, Basil and Cyril—that the sword that pierced Mary’s soul (Luke 2:35) was the sword of doubt and unbelief—rather than accept that the early church understood that Mary was sinful, Livius spends his next three pages correcting Origen, as well as Basil and Cyril who agreed with him.

This raises the obvious question: if Tradition, according to Rome “transmits in its entirety the Word of God … to the successors of the apostles” (Catechism, 81), then how did Livius “know” that this tradition in particular was wrong? The answer is that only “traditions” that are consistent with Roman Catholic teaching are correct, and Roman Catholic teachings are based only on those “correct” Traditions. This is a paradox worthy of Escher himself. Tradition that is inconsistent with Roman Catholic teaching is just not considered Tradition.

For an illustration of this, consider how Fr. Juniper Carol resolved the paradox of Origen’s, Basil’s and Cyril’s teaching on “the sword of unbelief” that pierced Mary’s soul:

How to resolve our original paradox? It would seem that before [the Council of] Ephesus some prominent churchmen and some of the laity in Alexandria and Caesarea of Cappadocia, in Antioch and Caesarea of Palestine, … were not aware of an obligation to represent the Mother of God as utterly sinless…(Fr. Juniper Carol, Mariology, vol 2, p. 136, ©1957)

Yes, that is how Fr. Carol resolves the paradox—these “prominent churchmen” must not have been aware of the teachings of the church!

Of course, when Origen posits that Mary is “the New Eve” (p. 47), when Basil acknowledges that sacred relics ought to be venerated (p. 311), and when Cyril of Alexandria writes that “every faithful soul is saved” through Mary (p. 70), Fr. Livius finds them to be fully informed on the teachings of the church, and therefore authoritative as regards Tradition. Even though none of these doctrines are found in the Scriptures, the teachings are confidently offered as a basis for Roman Catholic beliefs and practices.

So Frs. Juniper and Livius really have not resolved the paradox at all—they have merely changed their focus to a different part of Escher’s Drawing Hands. We find it particularly ironic, therefore, that Origen believed emphatically that his view on Mary’s sinfulness “differs in no respect from … apostolic tradition”:

…so, seeing there are many who think they hold the opinions of Christ, and yet some of these think differently from their predecessors, yet as the teaching of the Church, transmitted in orderly succession from the apostles, and remaining in the Churches to the present day, is still preserved, that alone is to be accepted as truth which differs in no respect from ecclesiastical and apostolic tradition. (De Principiis, prol, ii.)

How ironic that Rome seeks to prove the ancient doctrine of its own infallibility at least in part based on this statement from Origen. It is indeed a tribute to Rome’s churchcraft that she can dismiss Origen for not being aware of ecclesiastical and apostolic tradition, while at the same time appealing to Origen to prove that the Roman Church is the sole repository of “ecclesiastical and apostolic tradition.”

When Roman apologists try to convince you that Roman Catholic teachings are based on Tradition as taught by the successors to the Apostles, show them Escher’s Drawing Hands, but label one hand “apostolic tradition” and the other hand “the teachings of the church.” Then ask which hand is the drawing hand. To answer the question will require a discipline that is completely foreign to the Roman apologists, for they must only choose only one. The truth is, the Roman apologist will not choose one hand or the other. Perpetuating, rather than resolving, the paradox, is the Roman apologists’ arme de choix. Christ’s sheep, however, are not fooled by this.

Follow

Follow

One thought on “How to resolve an historical paradox”